Advent Meditation 2024, Week 1

Advent Meditation, First Week of Advent 2024

In the post-Classical, or the Ecclesiastical Latin, period of the Latin language, the noun annunciatio (late 4th century CE, in the Vulgate translation of the Bible by St. Jerome) meant “a preaching of the Gospel”, a moment or instance of this having been done. It was only in the 7th century that this same noun came to mean the most consequential proclamation of the Gospel in all of human history:

From that point on, the noun annunciation meant that Annunciation, which “mystery” in the tradition of the Rosary stands in first position in front of all the rest of the “mysteries” 4 of the Rosary, five of them per category: Joyful, Luminous, Sorrowful, and Glorious.

Luke 1 (NJB): 26 In the sixth month the angel Gabriel was sent by God to a town in Galilee called Nazareth, 27 to a virgin betrothed to a man named Joseph, of the House of David; and the virgin’s name was Mary. 28 He went in and said to her, ‘Rejoice, you who enjoy God’s favour! The Lord is with you.’ 29 She was deeply disturbed by these words and asked herself what this greeting could mean, 30 but the angel said to her, ‘Mary, do not be afraid; you have won God’s favour.3

From that point on, the noun annunciation meant that Annunciation, which “mystery” in the tradition of the Rosary stands in first position in front of all the rest of the “mysteries” 4 of the Rosary, five of them per category: Joyful, Luminous, Sorrowful, and Glorious.

20. The first five decades, the “joyful mysteries”, are marked by the joy radiating from the event of the Incarnation. This is clear from the very first mystery, the Annunciation, where Gabriel's greeting to the Virgin of Nazareth is linked to an invitation to messianic joy: “Rejoice, Mary”. The whole of salvation history, in some sense the entire history of the world, has led up to this greeting. If it is the Father's plan to unite all things in Christ (cf. Eph 1:10), then the whole of the universe is in some way touched by the divine favour with which the Father looks upon Mary and makes her the Mother of his Son.5

But what interests me is the fact that the very first Evangelist was not St. Mark, though St. Mark is consistently credited with the invention of the literary form “gospel” (not a biography; not a chronicle; not a collection of random historical instances).6 No, the first Evangelist was the Archangel Gabriel – a created being like us but of a higher order, who is a more intensely vivid way of being real - whose words to Mary of Nazareth are the first words spoken by God to a human being in what came to be called the “new” Testament - “Rejoice, you who enjoy God’s favor (Χαῖρε, κεχαριτωμένη)! The Lord is with you.” (Luke 1:29)

In other words, before the noun “evangelist” came to designate the author of a literary work (thus, Evangelist, as in one of the four who wrote the Gospels), it referred to a way a person could speak in the power of the Holy Spirit … and the effect that caused in the hearer. Before Mary had heard the Archangel speak of a pregnancy and about who would be her incomparable son – what we usually mean by “the good news” (euangelion) - the Archangel simply greeted her in that way of his/her, in a way that profoundly affected her – “she was deeply disturbed by these words". Notice that all the “disturbing” parts had not yet been spoken to her!

Think of the (more rare) Christians whom we might call “the real deal” (not the pretenders), the people who bear a likeness to Elijah or John the Baptist or Jesus. We remember not so much what they say – the words – but how powerfully and deeply such people affect us spiritually through what they say and how they say it. There is far more through such people than is in them. To listen to such people is to be changed. Even more significant to us than their words beautifully delivered to our ears is who they are, the “ring of truth” in them, their humility and realness. Who they are unsettles our self-satisfied ways of being a good enough person. They can be kind of scary.

In other words, before the noun “evangelist” came to designate the author of a literary work (thus, Evangelist, as in one of the four who wrote the Gospels), it referred to a way a person could speak in the power of the Holy Spirit … and the effect that caused in the hearer. Before Mary had heard the Archangel speak of a pregnancy and about who would be her incomparable son – what we usually mean by “the good news” (euangelion) - the Archangel simply greeted her in that way of his/her, in a way that profoundly affected her – “she was deeply disturbed by these words". Notice that all the “disturbing” parts had not yet been spoken to her!

Hebrews 4 (NJB): 12 The word of God is something alive and active: it cuts more incisively than any two-edged sword: it can seek out the place where soul is divided from spirit, or joints from marrow; it can pass judgement on secret emotions and thoughts. 13 No created thing is hidden from him; everything is uncovered and stretched fully open to the eyes of the one to whom we must give account of ourselves.7

Think of the (more rare) Christians whom we might call “the real deal” (not the pretenders), the people who bear a likeness to Elijah or John the Baptist or Jesus. We remember not so much what they say – the words – but how powerfully and deeply such people affect us spiritually through what they say and how they say it. There is far more through such people than is in them. To listen to such people is to be changed. Even more significant to us than their words beautifully delivered to our ears is who they are, the “ring of truth” in them, their humility and realness. Who they are unsettles our self-satisfied ways of being a good enough person. They can be kind of scary.

I would have loved to have been able to sit with Mary and to ask her about that day when the Archangel appeared to her. Maybe someday she will invite me to that.

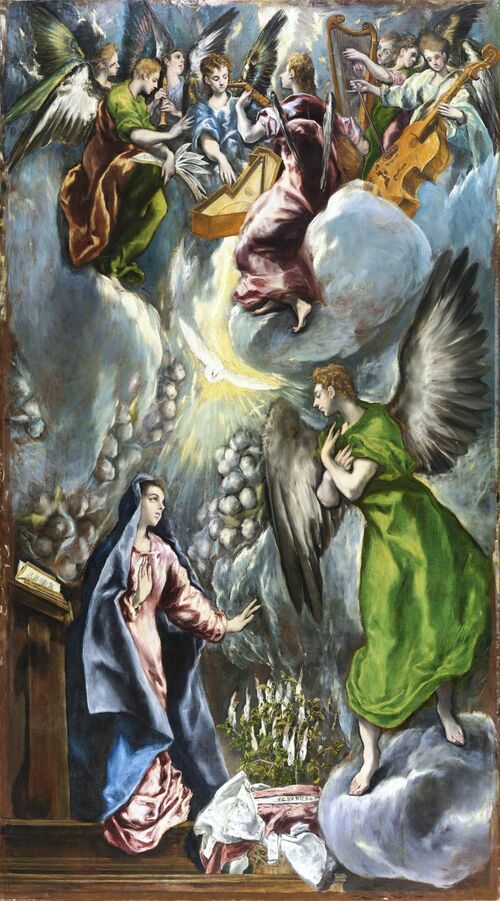

Perhaps El Greco was given that chance by Mary who let herself be known to him in his prayerful contemplation of the Annunciation (referring to the painting above).

Consider these three points about El Greco’s painting.

First, by observing carefully Mary’s reaction, what do you conclude is the “moment” El Greco is capturing within the whole scene articulated by Luke (1:26-38)? Has the Archangel just at that moment appeared to Mary, so that he gives us her first reaction? Or, has the Archangel already detailed for her what God would be doing with her pregnancy and her son to be born, if she would say “Yes”? Or is this the moment, after all has been said, when Mary says (v38): “You see before you the Lord’s servant, let it happen to me as you have said”?

Second, notice the location of the “dove”, the Holy Spirit shining with Light – “Let there be light, and there was light” (Genesis 1:3). It hovers not in between, as if the Archangel is speaking through the Holy Spirit. Rather, it hovers over the relationship that the Spirit effects between Mary and the Archangel. There is no authentic Word of God able to be understood or spoken sufficiently outside a context of friendship. Friendship first; then the Word - “living and active, cutting more sharply than a two-edged sword.”

Perhaps El Greco was given that chance by Mary who let herself be known to him in his prayerful contemplation of the Annunciation (referring to the painting above).

Consider these three points about El Greco’s painting.

First, by observing carefully Mary’s reaction, what do you conclude is the “moment” El Greco is capturing within the whole scene articulated by Luke (1:26-38)? Has the Archangel just at that moment appeared to Mary, so that he gives us her first reaction? Or, has the Archangel already detailed for her what God would be doing with her pregnancy and her son to be born, if she would say “Yes”? Or is this the moment, after all has been said, when Mary says (v38): “You see before you the Lord’s servant, let it happen to me as you have said”?

Second, notice the location of the “dove”, the Holy Spirit shining with Light – “Let there be light, and there was light” (Genesis 1:3). It hovers not in between, as if the Archangel is speaking through the Holy Spirit. Rather, it hovers over the relationship that the Spirit effects between Mary and the Archangel. There is no authentic Word of God able to be understood or spoken sufficiently outside a context of friendship. Friendship first; then the Word - “living and active, cutting more sharply than a two-edged sword.”

Third, we might with good reason have assumed that the “heavenly host” mentioned by Luke, who thronged the sky over Bethlehem (Luke 2:13 – “And all at once with the angel there was a great throng of the hosts of heaven, praising God. …”) were singing their praises, and likely the words were poetry: “Hark! The herald angels sing….” (Charles Wesley, 1739) But perhaps it had not occurred to us that the angels, in a similar festive mood, put together a baroque orchestra on that day Mary and the Archangel spoke, playing overhead a work of such sweetness and of such longing as to leave us, if we had been there that day, in tears, speechless with wonder. Why, do you suppose that the artist painted that heavenly orchestra floating above the two? Why is Music there? Did Mary reveal something to El Greco not recorded in Luke’s Gospel, who said to him something to this effect: “It is hard to explain. But what I felt in that moment with the Archangel were feelings so intensely full of longing that it was as if I could hear it – my longing becoming Music.” And did she then leave it up to El Greco to paint it as he judged best?

In conclusion, I share these lines that finish an astonishing poem called “Annunciation” by the contemporary poet, Maria Howe (the real deal). Mary is speaking:

Happy first week of Advent everyone.

In conclusion, I share these lines that finish an astonishing poem called “Annunciation” by the contemporary poet, Maria Howe (the real deal). Mary is speaking:

As one turns a mirror to flash the light to where

it isn’t – I was blinded like that – and swam

in what shone at me

only able to endure it by being no one and so

specifically myself I thought I’d die

from being loved like that.8

Happy first week of Advent everyone.

Notes

1 Grove Art (Oxford Online) at “El Greco” - The tendency towards a spectral treatment of lighting, and its effect on human forms within vertiginous compositions where mass and space merge, is found particularly in the canvases—showing epiphanies of God on earth—for the retable at the Colegio de Doña María de Aragón: the Incarnation and Baptism (Madrid, Prado), the Adoration of the Shepherds (Bucharest, N. Mus. A.), and perhaps also the Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Pentecost (Madrid, Prado). In these he achieved an extraordinary sense of the miraculous, maybe deriving from the mystical thinking of the preacher Alfonso de Orozco (1500–91) or perhaps from El Greco’s personal vision of the immanence of the divine.

2 See at Wikimedia: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anunciacion_Prado(2).jpg. This painting in the center panel of the high altar. To one side of that central panel, he painted the Adoration of the Shepherd and on the other side he painted the Baptism of Jesus. This high altar is in the Chapel of the Colegio de Encarnación donated by Doña María de Córdoba y Aragón in Madrid, Spain.

2 See at Wikimedia: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anunciacion_Prado(2).jpg. This painting in the center panel of the high altar. To one side of that central panel, he painted the Adoration of the Shepherd and on the other side he painted the Baptism of Jesus. This high altar is in the Chapel of the Colegio de Encarnación donated by Doña María de Córdoba y Aragón in Madrid, Spain.

3 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Lk 1:26–30.

4 Saint (Pope) John Paul II – Apostolic Letter “Rosarium Virginis Mariae” - 11. … The memories of Jesus, impressed upon her heart, were always with her [Mary, his mother], leading her to reflect on the various moments of her life at her Son's side. In a way those memories were to be the “rosary” which she recited uninterruptedly throughout her earthly life. Even now, amid the joyful songs of the heavenly Jerusalem, the reasons for her thanksgiving and praise remain unchanged. They inspire her maternal concern for the pilgrim Church, in which she continues to relate her personal account of the Gospel. Mary constantly sets before the faithful the “mysteries” of her Son, with the desire that the contemplation of those mysteries will release all their saving power. In the recitation of the Rosary, the Christian community enters into contact with the memories and the contemplative gaze of Mary.

5 Saint (Pope) John Paul II – Apostolic Letter “Rosarium Virginis Mariae”. From the Vatican, on the 16th day of October in the year 2002, the beginning of the twenty- fifth year of my Pontificate.

4 Saint (Pope) John Paul II – Apostolic Letter “Rosarium Virginis Mariae” - 11. … The memories of Jesus, impressed upon her heart, were always with her [Mary, his mother], leading her to reflect on the various moments of her life at her Son's side. In a way those memories were to be the “rosary” which she recited uninterruptedly throughout her earthly life. Even now, amid the joyful songs of the heavenly Jerusalem, the reasons for her thanksgiving and praise remain unchanged. They inspire her maternal concern for the pilgrim Church, in which she continues to relate her personal account of the Gospel. Mary constantly sets before the faithful the “mysteries” of her Son, with the desire that the contemplation of those mysteries will release all their saving power. In the recitation of the Rosary, the Christian community enters into contact with the memories and the contemplative gaze of Mary.

5 Saint (Pope) John Paul II – Apostolic Letter “Rosarium Virginis Mariae”. From the Vatican, on the 16th day of October in the year 2002, the beginning of the twenty- fifth year of my Pontificate.

6 Gospel, Gospels, the English translation of the Greek euangelion, which means ‘good news.’ In the NT it refers to the good news preached by Jesus that the Kingdom of God is at hand (Mark 1:15) and the good news of what God has done on behalf of humanity in Jesus (Rom. 1:3–5). The background for the noun is found in the OT where the verbal form ‘to bring good news’ or ‘to announce good news’ appears rather than the noun. [Paul J. Achtemeier, Harper & Row and Society of Biblical Literature, in Harper’s Bible Dictionary (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1985), 354.]

7 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Heb 4:12–13.

7 The New Jerusalem Bible (New York; London; Toronto; Sydney; Auckland: Doubleday, 1990), Heb 4:12–13.

8 Maria Howe, New and Selected Poems (2024), page 118.

Recent

Categories

Tags

Archive

2026

2025

January

March

June

October

2024

January

March

September

October

2023

March

November

2022

2021

2020

1 Comment

Perhaps shamefully, this is the first time I've ever paused to consider the Archangel in this story as feminine. I love that possibility so much.