The Lenten Meditations 2024, Week 2

Pain

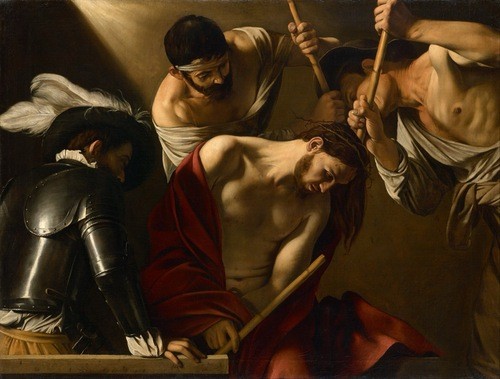

The Crowning with Thorns (1602/1604 or 1607) by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Hangs in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Hangs in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

In everyday conversation we often tend to use the words “pain” and “suffering” interchangeably. We may say, “My arthritis is causing me pain”, but just as likely we might also say, “I’ve been really suffering with my arthritis lately”. And we would mean much the same thing. In both instances, when we are talking about pain and suffering, we are attempting to express the inward reality that something is hurting us, and our English language does not much differentiate between the two terms.

But in the spiritual life, and particularly when we are contemplating the Passion of Jesus Christ, it is worth wondering in a deeper-than-usual way about whether “pain” and “suffering” are necessarily the same thing. Is this just a matter of semantics, or does Jesus point us towards a more complex, hidden relationship between these two seemingly transposable words?

In today’s Lenten Meditation we will explore this question together as we listen in on a passage from the Gospel of Mark:

So much pain is contained in this short passage; and if we read through it too quickly we can become anesthetized to the meaning of it. We must activate the powers of our imagination to really feel, on a visceral level, what Jesus experienced here; relentless, merciless pain. There is no doubt that the Romans knew what they were doing, and pain was an experience they could deliver with lethal acumen.

It is valuable, yes, to spend time entering into the pain, mental and physical, that Jesus endured, so that we may become closer to him and love him all the more. However, it is also possible to get tripped up if we over-emphasize Jesus’ pain as the focal point of his Passion. The power of what Jesus accomplished, our redemption and salvation, was not achieved through his pain; pain in itself is not transformative. If I stumble and fall into a blackberry bush and am pierced by thorns, as Jesus was, or accidentally hammer a nail through my hand while woodworking, it would certainly hurt, but it would not be revelatory. And, not to steal Jesus’ thunder, but tens of thousands of people were scourged and crucified; unimaginable as it is, he was not unique in that aspect. Yet his Passion, and only his, reformed the relationship between God and man forever. How?

It was not the pain Jesus experienced but the meaning he placed in his pain that is so remarkable in the Passion story; it was for something. Love and intention and faith imbued every moment of that pain. He made it matter. The crown of thorns, the whip, the nails, even the cross, are not what should capture our attention. We’re meant to notice Jesus, and how he destroyed the power of those terrifying weapons of torture by turning them into profound expressions of love. That is when pain becomes true suffering, when we offer our pain to God and say, “please use this pain and make with it something beautiful”. We transform our pain into suffering, and then the suffering transforms us; it can even transform the world.

So we see that suffering is a word that is really much more significant than pain; it represents not just the facts of what has hurt us but the relationship we form with those facts. Let me explain this another way. Recently my children checked out a library book called The Storyteller’s Handbook. The Storyteller’s Handbook has no words, only pictures: busy, quirky scenes showing nautilus shells flying in the air over a boy with a boat, or a yellow door where a bunny is handing out scrolls to a variety of wild beasts, and various other whimsical setups, the idea of the book being that the wordless illustrations should inspire you to create your own tales. When I looked at the drawings, my logical grown-up mind was limited to just describing what I saw; I created not a story, but a list of facts about each picture. My children, however, looked at the illustrations and immediately launched into incredible stories: they created mythical legends and epic tales of adventure and wonder that just astonished me. My little ones did not report facts; they connected the facts so that they formed relationships, thereby making meaning out of what they saw.

I think our experience with The Storyteller’s Handbook is an apt metaphor for the difference between pain and suffering. Pain is one of the inevitable facts of life: we break a wrist, we lose a job, we’re betrayed by a friend. It happens. But suffering is the hard work of meaning-making, the story we choose to create around our pain, a story that can tell how we became deeper, wiser, more beautiful, and more Christlike only if we were willing to be transformed by suffering. We don’t like the pain; we didn’t ask for it, and we don’t want it- but when it comes anyway, we can suffer in the example of Jesus, and we can make that pain matter.

So, my invitation to you, as I send you off into the wilds of this second week of Lent, is to consider something in your life currently that is causing you pain. How can that pain become suffering—in the pattern of Christ’s pain—so that it is suffered for something, or someone, in such a way that it connects you more deeply to the broader human family and the healing of the whole world? Suffering for a meaningful cause does not make our pain go away, and it certainly doesn’t fix our pain or even alleviate it; but it does mean that our pain won’t be wasted. So how will you make your pain matter?

I’ll close now with a passage from the Apostolic Letter Salvifici Doloris, on the Christian meaning of human suffering, written 40 years ago by Pope John Paul II:

Thank you for listening to the Lenten Meditations. May the time you spend side by side with the suffering Christ this Lent bring you ever closer to his beautiful heart. Amen.

But in the spiritual life, and particularly when we are contemplating the Passion of Jesus Christ, it is worth wondering in a deeper-than-usual way about whether “pain” and “suffering” are necessarily the same thing. Is this just a matter of semantics, or does Jesus point us towards a more complex, hidden relationship between these two seemingly transposable words?

In today’s Lenten Meditation we will explore this question together as we listen in on a passage from the Gospel of Mark:

Wanting to satisfy the crowd, Pilate released Barabbas to them. He had Jesus scourged, and handed him over to be crucified. The soldiers led Jesus away into the palace (that is, the Praetorium) and called together the whole company of soldiers. They put a purple robe on him, then twisted together a crown of thorns and set it on him. And they began to call out to him, “Hail, king of the Jews!” Again and again they struck him on the head with a staff and spit on him. Falling on their knees, they paid homage to him. And when they had mocked him, they took off the purple robe and put his own clothes on him. Then they led him out to crucify him. (Mark 15:15-20)

So much pain is contained in this short passage; and if we read through it too quickly we can become anesthetized to the meaning of it. We must activate the powers of our imagination to really feel, on a visceral level, what Jesus experienced here; relentless, merciless pain. There is no doubt that the Romans knew what they were doing, and pain was an experience they could deliver with lethal acumen.

It is valuable, yes, to spend time entering into the pain, mental and physical, that Jesus endured, so that we may become closer to him and love him all the more. However, it is also possible to get tripped up if we over-emphasize Jesus’ pain as the focal point of his Passion. The power of what Jesus accomplished, our redemption and salvation, was not achieved through his pain; pain in itself is not transformative. If I stumble and fall into a blackberry bush and am pierced by thorns, as Jesus was, or accidentally hammer a nail through my hand while woodworking, it would certainly hurt, but it would not be revelatory. And, not to steal Jesus’ thunder, but tens of thousands of people were scourged and crucified; unimaginable as it is, he was not unique in that aspect. Yet his Passion, and only his, reformed the relationship between God and man forever. How?

It was not the pain Jesus experienced but the meaning he placed in his pain that is so remarkable in the Passion story; it was for something. Love and intention and faith imbued every moment of that pain. He made it matter. The crown of thorns, the whip, the nails, even the cross, are not what should capture our attention. We’re meant to notice Jesus, and how he destroyed the power of those terrifying weapons of torture by turning them into profound expressions of love. That is when pain becomes true suffering, when we offer our pain to God and say, “please use this pain and make with it something beautiful”. We transform our pain into suffering, and then the suffering transforms us; it can even transform the world.

So we see that suffering is a word that is really much more significant than pain; it represents not just the facts of what has hurt us but the relationship we form with those facts. Let me explain this another way. Recently my children checked out a library book called The Storyteller’s Handbook. The Storyteller’s Handbook has no words, only pictures: busy, quirky scenes showing nautilus shells flying in the air over a boy with a boat, or a yellow door where a bunny is handing out scrolls to a variety of wild beasts, and various other whimsical setups, the idea of the book being that the wordless illustrations should inspire you to create your own tales. When I looked at the drawings, my logical grown-up mind was limited to just describing what I saw; I created not a story, but a list of facts about each picture. My children, however, looked at the illustrations and immediately launched into incredible stories: they created mythical legends and epic tales of adventure and wonder that just astonished me. My little ones did not report facts; they connected the facts so that they formed relationships, thereby making meaning out of what they saw.

I think our experience with The Storyteller’s Handbook is an apt metaphor for the difference between pain and suffering. Pain is one of the inevitable facts of life: we break a wrist, we lose a job, we’re betrayed by a friend. It happens. But suffering is the hard work of meaning-making, the story we choose to create around our pain, a story that can tell how we became deeper, wiser, more beautiful, and more Christlike only if we were willing to be transformed by suffering. We don’t like the pain; we didn’t ask for it, and we don’t want it- but when it comes anyway, we can suffer in the example of Jesus, and we can make that pain matter.

So, my invitation to you, as I send you off into the wilds of this second week of Lent, is to consider something in your life currently that is causing you pain. How can that pain become suffering—in the pattern of Christ’s pain—so that it is suffered for something, or someone, in such a way that it connects you more deeply to the broader human family and the healing of the whole world? Suffering for a meaningful cause does not make our pain go away, and it certainly doesn’t fix our pain or even alleviate it; but it does mean that our pain won’t be wasted. So how will you make your pain matter?

I’ll close now with a passage from the Apostolic Letter Salvifici Doloris, on the Christian meaning of human suffering, written 40 years ago by Pope John Paul II:

To suffer means to become particularly susceptible, particularly open to the working of the salvific powers of God, offered to humanity in Christ. In him God has confirmed his desire to act especially through suffering, which is man's weakness and emptying of self, and he wishes to make his power known precisely in this weakness and emptying of self. This also explains the exhortation in the First Letter of Peter: "Yet if one suffers as a Christian, let him not be ashamed, but under that name let him glorify God."

Thank you for listening to the Lenten Meditations. May the time you spend side by side with the suffering Christ this Lent bring you ever closer to his beautiful heart. Amen.

Recent

Categories

Tags

Archive

2026

January

2025

January

March

June

October

2024

January

March

September

October

2023

March

November

2022

2021

2020

2019

2 Comments

Tha k you TarA, profound thinking.it helped me think about something I can offer to Jesus with

My little suffering.

Kathy Jackson

Thanks Tara. Very helpful information presented in a way that makes it easy to understand and to relate to your insights.