The Lenten Meditations 2020, Week 1

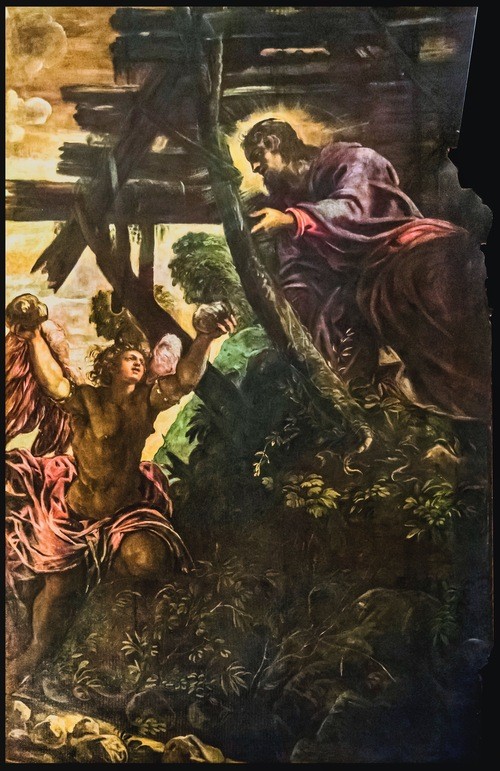

Jacopo Tintoretto (d. 1594)[1], The Temptation of Christ (1578-1581)

in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, Sala Superior[2]

in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, Sala Superior[2]

Poem

Midway in the journey of our life

I came to myself in a dark wood,

for the straight way was lost.

Ah, how hard it is to tell

the nature of that wood, savage, dense and harsh -

the very thought of it renews my fear!

It is so bitter death is hardly more so.

But to set forth the good I found

I will recount the other things I saw.[3]

I came to myself in a dark wood,

for the straight way was lost.

Ah, how hard it is to tell

the nature of that wood, savage, dense and harsh -

the very thought of it renews my fear!

It is so bitter death is hardly more so.

But to set forth the good I found

I will recount the other things I saw.[3]

Points

FIRST POINT – How we name our experiences, or those of Jesus in the Gospels for that matter, reveals the degree of insight we have, or not, into what actually is the point of a significant experience. Do you think that, for example, “The Temptation of Christ” gets to the heart of what is going on in Matthew 4:1-11? But doesn’t that title put too much weight on the temptation, and therefore upon the Tempter, rather than it does on the God-Man who utterly defeated Satan’s challenge, three times? Might a better title be “How Christ Disappointed (!) Satan”? Others call this “The Temptation of Jesus,” which is the title we see most often in Bibles. The problem continues with its emphasis on the temptation (why in the singular?). And, that title seems to introduce the possibility, by using Jesus’ personal earthly name, that this temptation was aimed solely at His human nature (Jesus) not at his divine nature (Christ).[4] Then, others offer the title “Jesus is Tested in the Wilderness” (NIV). Better! Here the emphasis is on Jesus – His name in first position in the title. And the use of the verb “tested” opens the meaning to include for Jesus not solely a moral moment (temptation is a moral word closely linked to sinning) but a growth moment. On the one hand, we consider a person’s falling for a temptation as a decision that weakens him or her; while, on the other hand, we consider a testing as something designed, and perfectly timed by a Teacher or Coach or Parent, to strengthen the person who accepts to face such a test. Samuel Johnson’s 18th century A Dictionary of the English Language (published 1755) defines the noun “test” – “That by which the existence, quality, or genuineness of anything is or may be determined; ‘means of trial’ (Johnson); hence, in phrases to bring or put to the test, to bear or stand the test, the testing or trial of the quality of anything; examination, trial, proof.”[5] The title “Jesus is Tested…” then leaves open the possibility for us to consider that this moment was about the divine Father, Who let Satan test the God-Man, and right at this moment, so that the quality, genuineness, and strength of the God-Man might blaze forth, presenting itself to a startled and discomfited[6] Satan. Finally, one commentary gives the title “The Testing of the Son of God”[7] (my favorite among the titles). Why do you think this might aim your contemplation more sufficiently to what really is going on in this Gospel scene, aimed at what the Father is up to … in contrast to what Satan was up to here?

SECOND POINT – Let us look closely at Jacopo Tintoretto’s painting (above). The easiest of the three temptations to paint is the one that Tintoretto painted:

But perhaps he painted this temptation not for that reason, but because there was during Tintoretto’s life (d. 1594) widespread famine in Europe – thus the particular need for “bread” – which spawned the temptation in human beings to turn against each other in war – the ancient bloodlust in our arteries surging – instead of toward habits of mutual helping and sharing – 20 They all ate and were satisfied, and the disciples picked up twelve basketfuls of broken pieces that were left over. [9]

Tintoretto, and rightly, contemplates the Gospel not abstractly (in a Time long ago; in a place far away, etc.) but concretely, looking into his own life and social circumstances to see where the Father was “testing” him through experiences of scarcity. What did Jesus do with His experience of a self-induced scarcity (or better, an experience of testing set for Him by the impelling[11] Holy Spirit): scarcity of context – the barren waste of desert – and scarcity of resources– food? What do you do with your experiences of scarcity and with the “testing” they present?

THIRD POINT – Perhaps St. Augustine’s masterwork is his City of God (written from 413-427 CE).[12] In it he articulates a philosophy of History constituted by two stories, or two logics, with “history” meaning an account of how these two stories and two logics vie[13] through Time. There is the love of Self in persons that is their over-riding, guiding reason (logic), which causes through Time so much damage and hurt to human relationships. There is, in contrast, the love of God that is the over-riding, guiding reason (logic) in persons who work, who sacrifice themselves for, God’s purposes in our world. Their driving commitment is “on Earth / as it is in Heaven” (e.g., Matthew 6:9ff).

At the very start of the God-Man’s public life, the Holy Spirit impelled Him into the wilderness to be tested (i.e., to set His deepest sources of strength ablaze with luminosity), so that He would be ready to be tested by the author of the world’s (not God’s) logic. There, the God-Man, stripped of all the “props” that the world expects a strong, well-resourced, and confident person to have, was offered His chance to embrace the logic of the unredeemed world … which beautifully He rejected, at every point. One particularly acute commentator on the Gospel of Matthew writes:

Where in your life, and your typical way of proceeding with it, is the logic of the Kingdom of God most consistently active in how you make decisions?

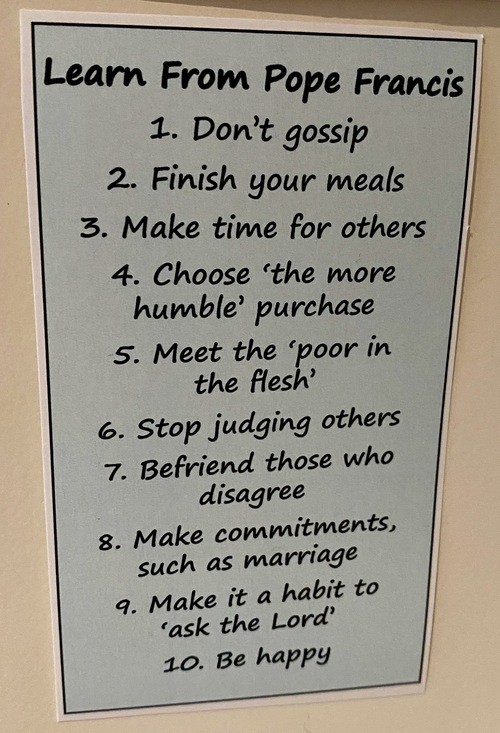

SETTING A TASK FOR WEEK ONE – Consider this from Pope Francis that describes the logic of the Kingdom of God. I found this “Summons” taped to the wall next to the work desk of my sister-in-law, Leslie:

SECOND POINT – Let us look closely at Jacopo Tintoretto’s painting (above). The easiest of the three temptations to paint is the one that Tintoretto painted:

3 The temptery came to him and said, “If you are the Son of God,z tell these stones to become bread.” 4 Jesus answered, “It is written: ‘Man shall not live on bread alone, but on every word that comes from the mouth of God.’b”a [8]

But perhaps he painted this temptation not for that reason, but because there was during Tintoretto’s life (d. 1594) widespread famine in Europe – thus the particular need for “bread” – which spawned the temptation in human beings to turn against each other in war – the ancient bloodlust in our arteries surging – instead of toward habits of mutual helping and sharing – 20 They all ate and were satisfied, and the disciples picked up twelve basketfuls of broken pieces that were left over. [9]

Cooling during the Cold Phase in Europe (1560-1660 AD) reduced crop yields by shortening the growing season and shrinking the cultivated land area. Although agricultural production decreased or became stagnant in a cold climate, population size still grew, leading to an increase in grain price and an increased demand on food supplies. Inflating grain prices led to hardships for many, and triggered social problems and conflicts such as rebellions, revolutions, and political reforms…. Many of these disturbances led to armed conflicts, and the number of wars increased forty-one percent during the Cold Phase. During the latter portion of the Cold Phase, the number of wars decreased, but the wars lasted longer and were far more lethal—most notable was the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), where fatalities were more than twelve times that of the conflicts between 1500-1619…. Famine became more frequent too. Nutrition deteriorated, and the average height of Europeans shrunk 2cm by the late 16th century. As temperatures began to rise again after 1650, so did the average height.[10]

Tintoretto, and rightly, contemplates the Gospel not abstractly (in a Time long ago; in a place far away, etc.) but concretely, looking into his own life and social circumstances to see where the Father was “testing” him through experiences of scarcity. What did Jesus do with His experience of a self-induced scarcity (or better, an experience of testing set for Him by the impelling[11] Holy Spirit): scarcity of context – the barren waste of desert – and scarcity of resources– food? What do you do with your experiences of scarcity and with the “testing” they present?

THIRD POINT – Perhaps St. Augustine’s masterwork is his City of God (written from 413-427 CE).[12] In it he articulates a philosophy of History constituted by two stories, or two logics, with “history” meaning an account of how these two stories and two logics vie[13] through Time. There is the love of Self in persons that is their over-riding, guiding reason (logic), which causes through Time so much damage and hurt to human relationships. There is, in contrast, the love of God that is the over-riding, guiding reason (logic) in persons who work, who sacrifice themselves for, God’s purposes in our world. Their driving commitment is “on Earth / as it is in Heaven” (e.g., Matthew 6:9ff).

Augustine’s tripartite scheme is inspired by the Bible and corresponds to what now often goes under the name of “salvation history.” It should be noted that the two cities in question are not empirical entities, comparable to cities in the ordinary sense and identifiable by their geographical boundaries. They are cities in a mystical sense—mystice (15.1.1). Citizenship in one or the other is determined, not by the accidents of one’s birth, parental lineage, or place of residence, but by the object of one’s love or the end to which all of one’s actions are subordinated: in one case, “the love of God to the contempt of oneself”; in the other case, “the love of oneself to the contempt of God” (14.28).[14]

At the very start of the God-Man’s public life, the Holy Spirit impelled Him into the wilderness to be tested (i.e., to set His deepest sources of strength ablaze with luminosity), so that He would be ready to be tested by the author of the world’s (not God’s) logic. There, the God-Man, stripped of all the “props” that the world expects a strong, well-resourced, and confident person to have, was offered His chance to embrace the logic of the unredeemed world … which beautifully He rejected, at every point. One particularly acute commentator on the Gospel of Matthew writes:

If Satan is the hero of the world, the lord of the earthly minded who proposes disruption of the divine order at every step, Christ is the divine Hero who comes to confront Satan’s logic with stout clear-headedness and humility. The desert offers an occasion for two diametrically opposed solutions to the plight of man: either capitulation to the comforts of the satanic attitude—food, power, possessions—or surrender to the mercy of God’s providence. The desert is the place of utter poverty and therefore, potentially, of heroic trust in God. A Hassidic rabbi, Moshe Loeb, once said: “How easy it is for a poor person to trust in God! In what else is he or she to trust? And how difficult it is for a rich person to trust in God! All his or her possessions are crying out to him or her: ‘Trust in me!’”[15]

Where in your life, and your typical way of proceeding with it, is the logic of the Kingdom of God most consistently active in how you make decisions?

SETTING A TASK FOR WEEK ONE – Consider this from Pope Francis that describes the logic of the Kingdom of God. I found this “Summons” taped to the wall next to the work desk of my sister-in-law, Leslie:

Notes

[1] Benezit Dictionary of Artists: Jacopo Robusti Tintoretto was the son of the Venetian dyer Battisto Robusti, from whom he got his appellation ‘Tintoretto’ or ‘little dyer’. He was known for his quick, abbreviated style and dramatic compositions. Though he never achieved great wealth, he enjoyed a long and productive career in Venice, employing several of his eight children in his studio… The following year he completed St Roch Healing the Plague Victims (1549) for the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. These works demonstrate Tintoretto’s use of full-body gestures and dramatic chiaroscuro lighting as storytelling devices, and they mark his entry into more prestigious social circles…. The canvases demonstrate Tintoretto’s renewed interest in unusual and dramatic compositional spaces. The curious use of light, space and colour convey an insubstantial and visionary atmosphere—a quality that he continued to explore in his cycle for the Scuola di San Rocco. See: https://doi.org/10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.B00183123.

[2] Find image at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paintings_by_Tintoretto_in_Scuola_Grande_di_San_Rocco_-_Sala_superiore_-_The_Temptation_of_Christ.jpg.

[3] The opening lines of Inferno, Canto 1, by Dante, translation at the Princeton Dante Project. Go to: http://etcweb.princeton.edu/dante/pdp/. In the strictly observed architectural structure of Dante’s whole Divine Comedy (Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso), only Inferno has one extra Canto – the first one, from which these lines are taken. The point is that Canto 1 of Inferno is an account of a failed spiritual journey, of a journey in which he is still trying to do it on his own, to finally get it right. The true spiritual journey can begin when we have exhausted our own efforts to get it right, finally surrendering ourselves to the Friend Who comes to lead us. The Friend knows the Way.

[4] This is a stretch for me to suggest this. But I do believe that many people could not possibly imagine that the “divine” nature of Jesus Christ could be tempted by Satan … surely, not that! My point is that we human beings are always in danger of misunderstanding, and therefore misconstruing, the unity of both divine and human natures in the personhood of Jesus Christ.

[5] Entry at “test” in the Oxford English Dictionary.

[6] The Oxford English Dictionary at the 15th century verb “to discomfit” – “To frustrate the plans or hopes of, thwart, foil; to throw into perplexity, dejection, or confusion. Now chiefly in weakened sense: to cause unease, embarrassment, or discomfort to; to disconcert.”

[7] “All three synoptic writers record an experience of Jesus in the wilderness in confrontation with the devil immediately after his baptismal revelation and before his return to Galilee. But while Mark presents only a brief tableau of the opposing forces, Matthew and Luke record a three-point dialogue between the tempter and Jesus which explores more deeply the nature of the “testing” involved, the details of which, if they are not purely imaginary, can only have come from Jesus’ own subsequent recalling of the event.” (R. T. France, The Gospel of Matthew, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publication Co., 2007), 126.

y 1 Th 3:5

z See Mt 3:17; 14:33; 16:16; 27:54; Mk 3:11; Lk 1:35; 22:70; Jn 1:34, 49; 5:25; 11:27; 20:31; Ac 9:20; Ro 1:4; 1 Jn 5:10–13, 20; Rev 2:18

b Deut. 8:3

a Dt 8:3; Jn 4:34

[8] The New International Version (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), Mt 4:3–4.

[9] The New International Version (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), Mt 14:20.

[10] See: https://arstechnica.com/science/2011/10/european-wars-famine-and-plagues-driven-by-climate/.

[11] The Oxford English Dictionary at the late-15th century verb “to impel” – “To drive, force, or constrain (a person) to some action, or to do something, by acting upon his mind or feelings; to urge on, incite.”

[12] “Written at intermittent intervals between 413 and 427 CE, the City of God is Augustine’s longest and most comprehensive work. It is also one of the foundational books of patristic literature. Its unique achievement is to have clarified Christianity’s ambiguous relationship to the temporal order and to have established, in opposition to some of the most influential Christian writers of the Constantinian era, its radical transcendence vis-à-vis the Roman Empire and, indeed, all possible regimes or political dispensations. Implied in Augustine’s position on this issue is a rejection of the classical notion of the city or its equivalents as self-sufficient totalities capable of fulfilling all of one’s basic needs and aspirations. Without renouncing their citizenship in the temporal society to which they belong, Christians form part of a universal, albeit invisible, society in which alone salvation can be attained. In order to defend his thesis, Augustine was forced to touch upon virtually every important aspect of Christian life and thought. This accounts for the encyclopedic character of the City of God, which frequently delves into matters that go well beyond the historical circumstances that dictated its composition.” [Ernest L. Fortin, “Civitate Dei, De,” ed. Allan D. Fitzgerald, Augustine through the Ages: An Encyclopedia (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999), 196.] Emphases were added by me.

[13] The Oxford English Dictionary at the 16th verb “to vie” – “To display, advance, practise, etc., in competition or rivalry with another person or thing; to contend or strive with in respect of (something).”

[14] Ernest L. Fortin, “Civitate Dei, De,” ed. Allan D. Fitzgerald, Augustine through the Ages: An Encyclopedia (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999), 196–197.

[15] Leiva, Erasmo. Fire of Mercy, Vol. 1, chapter “Temptation in the Wilderness”. Ignatius Press. Kindle Edition.

[2] Find image at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paintings_by_Tintoretto_in_Scuola_Grande_di_San_Rocco_-_Sala_superiore_-_The_Temptation_of_Christ.jpg.

[3] The opening lines of Inferno, Canto 1, by Dante, translation at the Princeton Dante Project. Go to: http://etcweb.princeton.edu/dante/pdp/. In the strictly observed architectural structure of Dante’s whole Divine Comedy (Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso), only Inferno has one extra Canto – the first one, from which these lines are taken. The point is that Canto 1 of Inferno is an account of a failed spiritual journey, of a journey in which he is still trying to do it on his own, to finally get it right. The true spiritual journey can begin when we have exhausted our own efforts to get it right, finally surrendering ourselves to the Friend Who comes to lead us. The Friend knows the Way.

[4] This is a stretch for me to suggest this. But I do believe that many people could not possibly imagine that the “divine” nature of Jesus Christ could be tempted by Satan … surely, not that! My point is that we human beings are always in danger of misunderstanding, and therefore misconstruing, the unity of both divine and human natures in the personhood of Jesus Christ.

[5] Entry at “test” in the Oxford English Dictionary.

[6] The Oxford English Dictionary at the 15th century verb “to discomfit” – “To frustrate the plans or hopes of, thwart, foil; to throw into perplexity, dejection, or confusion. Now chiefly in weakened sense: to cause unease, embarrassment, or discomfort to; to disconcert.”

[7] “All three synoptic writers record an experience of Jesus in the wilderness in confrontation with the devil immediately after his baptismal revelation and before his return to Galilee. But while Mark presents only a brief tableau of the opposing forces, Matthew and Luke record a three-point dialogue between the tempter and Jesus which explores more deeply the nature of the “testing” involved, the details of which, if they are not purely imaginary, can only have come from Jesus’ own subsequent recalling of the event.” (R. T. France, The Gospel of Matthew, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publication Co., 2007), 126.

y 1 Th 3:5

z See Mt 3:17; 14:33; 16:16; 27:54; Mk 3:11; Lk 1:35; 22:70; Jn 1:34, 49; 5:25; 11:27; 20:31; Ac 9:20; Ro 1:4; 1 Jn 5:10–13, 20; Rev 2:18

b Deut. 8:3

a Dt 8:3; Jn 4:34

[8] The New International Version (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), Mt 4:3–4.

[9] The New International Version (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), Mt 14:20.

[10] See: https://arstechnica.com/science/2011/10/european-wars-famine-and-plagues-driven-by-climate/.

[11] The Oxford English Dictionary at the late-15th century verb “to impel” – “To drive, force, or constrain (a person) to some action, or to do something, by acting upon his mind or feelings; to urge on, incite.”

[12] “Written at intermittent intervals between 413 and 427 CE, the City of God is Augustine’s longest and most comprehensive work. It is also one of the foundational books of patristic literature. Its unique achievement is to have clarified Christianity’s ambiguous relationship to the temporal order and to have established, in opposition to some of the most influential Christian writers of the Constantinian era, its radical transcendence vis-à-vis the Roman Empire and, indeed, all possible regimes or political dispensations. Implied in Augustine’s position on this issue is a rejection of the classical notion of the city or its equivalents as self-sufficient totalities capable of fulfilling all of one’s basic needs and aspirations. Without renouncing their citizenship in the temporal society to which they belong, Christians form part of a universal, albeit invisible, society in which alone salvation can be attained. In order to defend his thesis, Augustine was forced to touch upon virtually every important aspect of Christian life and thought. This accounts for the encyclopedic character of the City of God, which frequently delves into matters that go well beyond the historical circumstances that dictated its composition.” [Ernest L. Fortin, “Civitate Dei, De,” ed. Allan D. Fitzgerald, Augustine through the Ages: An Encyclopedia (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999), 196.] Emphases were added by me.

[13] The Oxford English Dictionary at the 16th verb “to vie” – “To display, advance, practise, etc., in competition or rivalry with another person or thing; to contend or strive with in respect of (something).”

[14] Ernest L. Fortin, “Civitate Dei, De,” ed. Allan D. Fitzgerald, Augustine through the Ages: An Encyclopedia (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999), 196–197.

[15] Leiva, Erasmo. Fire of Mercy, Vol. 1, chapter “Temptation in the Wilderness”. Ignatius Press. Kindle Edition.

Recent

Categories

Tags

Archive

2026

2025

January

March

June

October

2024

January

March

September

October

2023

March

November

2022

2021

2020

No Comments