The Lenten Meditations 2024, Week 4

Mercy

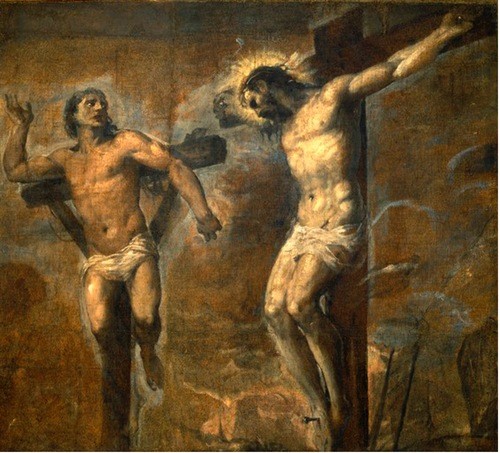

Christ and the Good Thief (1566) by Titian

Hangs in the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna in Bologna, Italy

Hangs in the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna in Bologna, Italy

We have explored previously in the Lenten Meditations the idea that suffering, in itself, is not inherently good. And yet, remarkably, when a thing is suffered well, it often inspires goodness; not only in ourselves, but in those who bear witness to our suffering. In his book The Problem of Pain author C.S. Lewis writes, “but if suffering is good ought it not to be pursued rather than avoided? I answer that suffering is not good in itself. What is good in any painful experience is, for the sufferer, his submission to the will of God, and, for the spectators, the compassion aroused in the acts of mercy to which it leads.” And indeed, God has imbued our suffering with the capacity to rouse others to profound works of mercy. In today’s meditation, we will seek to follow that thread, observing how mercy can become activated in the soul of a person in response to the suffering they see, and how God is always reaching through our suffering to try to awaken the hearts of others.

But first, what exactly is mercy? It’s a word we Christians throw around a lot, maybe without even fully understanding it. In the spiritual life, when we talk about being merciful, we must mean something more than merely just being nice, something deeper than just feeling bad for someone. The great theologian Thomas Aquinas has defined mercy as "the compassion in our hearts for another person's misery, a compassion which drives us to do what we can to help him”. So inherent in the concept of mercy is a response, not only at the level of the affect, but a response that is manifested in concrete action. We do not just feel mercy, we do mercy.

Let us observe how Jesus “did” mercy, as he responded to the suffering he saw here in the Gospel of Luke:

Jesus is really hurting here, on his cross, we can have no doubt about that. But what is remarkable is that his way of suffering does not cause him to retreat inward, more deeply into his own experience; it sends him outward, where his suffering meets the suffering of the one whom our tradition calls “the good thief”. Undoubtedly, we understand the suffering of others better when we ourselves have suffered. Jesus reaches out to the good thief, responding to his suffering with beautiful mercy when he says: “today you will be with me in paradise”. A truly merciful forgiveness, comfort, and encouragement, given in the darkest of places.

We, too, are built to respond to suffering, to feel it arouse in us a call to Christlike mercy, and then act as Jesus did. In our house we recently read a children’s book that illustrates this very response, called Gifts from the Enemy by Trudy Ludwig (the name is just a coincidence, she is no relation to my family.) Gifts from the Enemy tells the true story of Alter Wiener, who was 15 when he was captured by the Nazis. Wiener describes being forced to work in a concentration camp under brutal conditions and slowly starving to death. On the wall of a factory where he worked was a sign addressed to the German employees that said: “Do not look at the prisoners. Do not talk to the prisoners. Do not give anything to the prisoners. If you do, you will be DOOMED.”

And yet one day, a German worker did look at Wiener; she caught his eye, pointed to a box on the floor, and walked away. When Wiener was alone, he peeked under the box, and to his astonishment found a cheese sandwich waiting for him there. Despite knowing that she would be executed if she were discovered, the German woman left a sandwich under the box for him every day for 30 days, until he was transferred to another camp.

This woman’s choice to risk her own life to feed her enemy reminds us that even in the midst of calamity, God is still at work. At the very depths of human misery, mercy was alive and active; miraculously, against all odds, unimaginable suffering became the door through which God’s mercy was able to enter the world.

So, my invitation to you, as I send you off into the wilds of this fourth week of Lent, is to be merciful. Notice the suffering of others, and respond. While it is unlikely that we will ever do anything as dramatic as risking our life to feed someone, we are surrounded by so much need: to a lonely person, a phone call or visit may be just as precious as a cheese sandwich. To someone who is cold, a pair of warm, dry socks is the epitome of mercy. And to an exhausted and overwhelmed mother an offer of babysitting is—I promise you—like the embrace of God Himself.

I’ll close now with a passage from the Apostolic Letter Salvifici Doloris, on the Christian meaning of human suffering, written 40 years ago by Pope John Paul II:

Thank you for listening to the Lenten Meditations. May the time you spend side by side with the suffering Christ this Lent bring you ever closer to his beautiful heart. Amen.

But first, what exactly is mercy? It’s a word we Christians throw around a lot, maybe without even fully understanding it. In the spiritual life, when we talk about being merciful, we must mean something more than merely just being nice, something deeper than just feeling bad for someone. The great theologian Thomas Aquinas has defined mercy as "the compassion in our hearts for another person's misery, a compassion which drives us to do what we can to help him”. So inherent in the concept of mercy is a response, not only at the level of the affect, but a response that is manifested in concrete action. We do not just feel mercy, we do mercy.

Let us observe how Jesus “did” mercy, as he responded to the suffering he saw here in the Gospel of Luke:

Two other men, both criminals, were also led out with him to be executed. When they came to the place called the Skull, they crucified him there, along with the criminals—one on his right, the other on his left. Jesus said, “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.” And they divided up his clothes by casting lots. The people stood watching, and the rulers even sneered at him. They said, “He saved others; let him save himself if he is God’s Messiah, the Chosen One.” The soldiers also came up and mocked him. They offered him wine vinegar and said, “If you are the king of the Jews, save yourself.” There was a written notice above him, which read: this is the king of the jews. One of the criminals who hung there hurled insults at him: “Aren’t you the Messiah? Save yourself and us!” But the other criminal rebuked him. “Don’t you fear God,” he said, “since you are under the same sentence? We are punished justly, for we are getting what our deeds deserve. But this man has done nothing wrong.” Then he said, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” Jesus answered him, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise.” (Luke 23:32-43.)

Jesus is really hurting here, on his cross, we can have no doubt about that. But what is remarkable is that his way of suffering does not cause him to retreat inward, more deeply into his own experience; it sends him outward, where his suffering meets the suffering of the one whom our tradition calls “the good thief”. Undoubtedly, we understand the suffering of others better when we ourselves have suffered. Jesus reaches out to the good thief, responding to his suffering with beautiful mercy when he says: “today you will be with me in paradise”. A truly merciful forgiveness, comfort, and encouragement, given in the darkest of places.

We, too, are built to respond to suffering, to feel it arouse in us a call to Christlike mercy, and then act as Jesus did. In our house we recently read a children’s book that illustrates this very response, called Gifts from the Enemy by Trudy Ludwig (the name is just a coincidence, she is no relation to my family.) Gifts from the Enemy tells the true story of Alter Wiener, who was 15 when he was captured by the Nazis. Wiener describes being forced to work in a concentration camp under brutal conditions and slowly starving to death. On the wall of a factory where he worked was a sign addressed to the German employees that said: “Do not look at the prisoners. Do not talk to the prisoners. Do not give anything to the prisoners. If you do, you will be DOOMED.”

And yet one day, a German worker did look at Wiener; she caught his eye, pointed to a box on the floor, and walked away. When Wiener was alone, he peeked under the box, and to his astonishment found a cheese sandwich waiting for him there. Despite knowing that she would be executed if she were discovered, the German woman left a sandwich under the box for him every day for 30 days, until he was transferred to another camp.

This woman’s choice to risk her own life to feed her enemy reminds us that even in the midst of calamity, God is still at work. At the very depths of human misery, mercy was alive and active; miraculously, against all odds, unimaginable suffering became the door through which God’s mercy was able to enter the world.

So, my invitation to you, as I send you off into the wilds of this fourth week of Lent, is to be merciful. Notice the suffering of others, and respond. While it is unlikely that we will ever do anything as dramatic as risking our life to feed someone, we are surrounded by so much need: to a lonely person, a phone call or visit may be just as precious as a cheese sandwich. To someone who is cold, a pair of warm, dry socks is the epitome of mercy. And to an exhausted and overwhelmed mother an offer of babysitting is—I promise you—like the embrace of God Himself.

I’ll close now with a passage from the Apostolic Letter Salvifici Doloris, on the Christian meaning of human suffering, written 40 years ago by Pope John Paul II:

We could say that suffering, which is present under so many different forms in our human world, is also present in order to unleash love in the human person, that unselfish gift of one's "I" on behalf of other people, especially those who suffer. The world of human suffering unceasingly calls for, so to speak, another world: the world of human love; and in a certain sense man owes to suffering that unselfish love which stirs in his heart and actions.

Thank you for listening to the Lenten Meditations. May the time you spend side by side with the suffering Christ this Lent bring you ever closer to his beautiful heart. Amen.

Recent

Categories

Tags

Archive

2026

2025

January

March

June

October

2024

January

March

September

October

2023

March

November

2022

2021

2020

1 Comment

Thank you for the clarification of the word Mercy and the inspiring writing.