Letters to Peregrinus #55 - On the Wandering

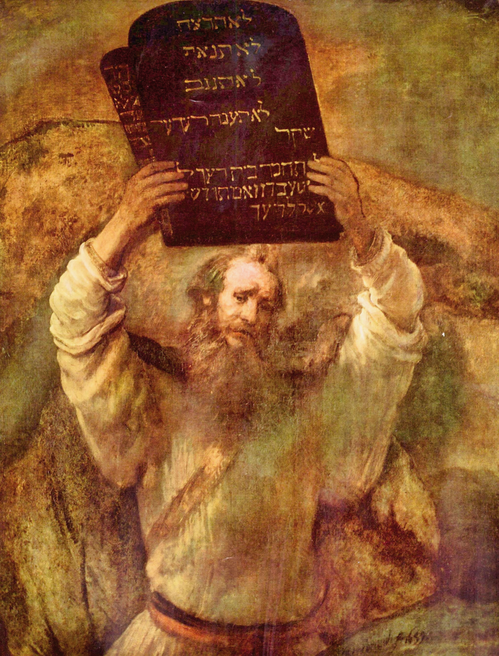

Rembrandt (1606-1669) – Moses with the Tablets of the Law (1659),

at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin

at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin

Doris Kearns Goodwin (b. 1943) - “If you interview five people about the same incident, and you see five different points of view, it makes you know what makes history so complicated. Something doesn’t just occur. It’s not like a scientific event. It’s a human event.”

John Jacob Niles (1892-1980) -

John Jacob Niles (1892-1980) -

I wonder as I wander out under the sky,

How Jesus, the Saviour, did come for to die.

For poor, ornery[1] people like you and like I

I wonder as I wander

Out under the sky.[2]

How Jesus, the Saviour, did come for to die.

For poor, ornery[1] people like you and like I

I wonder as I wander

Out under the sky.[2]

Johnny Cash (1932-2003)[3] – “You build on failure. You use it as a stepping stone. Close the door on the past. You don't try to forget the mistakes, but you don't dwell on them. You don't let them have any of your energy, or any of your time, or any of your space.”

Dear Peregrinus (the feast of St. Hilary of Poitiers[4]):

I am writing to you from one day beyond a day in Portland when we received the most rain ever recorded on that day. Perhaps with a certain mordant[5] reflectivity, I recalled yesterday as the rain poured down from the sky these lines from Genesis:

These lines mark the opening of that great and timeless Tale of the Great Flood (Genesis 6-9).

If one is not careful – and we humans are often not careful – then we, reading these lines, will fix our attention on God’s harsh judgment about us humans … and overlook utterly that God has the capacity to feel hurt!

In our cussed[7] self-absorption, we conclude that God is judgmental[8] (and His judgment of us scares us; and we think it unfair) rather than noticing that this expression of His mighty heart’s hurt is itself a practice of vulnerability towards us.

Yet God’s “vulnerability”[9] (literally, God’s ability to be “hurt” by human beings) becomes a delicate matter when we human beings have, in our intemperance,[10] lost the ability to understand how the hurt Someone who is truly good feels in the face of our gross moral failure can clarify the unchanging steadfastness in goodness of the offended (divine) Person. In other words, God’s “vulnerability” biblically articulated reveals Who and how God really is. His unchanging goodness is made more obvious to us who are habitually changeable and sometimes content to be cussed.

Suffering, the suffering of a good person, is the furnace in which the essence of a person is refined; what really matters to him or her reveals itself. God’s “hurt” does not confuse or change Him; it reveals Him!

Oh, Peregrinus, I need your example of careful thinking, because such a thing is so rare in our public life as Americans. Even when people appear to be offering reasons, they really are not. They, intemperately boiling with emotions too strong, imagine that their emotions are reasons, and so, are self-justifying!

My brother Bill put me in touch with the painting by Rembrandt that I have set at the head of this Letter. I wonder what you think about it. Here are four things that were catalyzed in me by a contemplation of that masterpiece.

I am writing to you from one day beyond a day in Portland when we received the most rain ever recorded on that day. Perhaps with a certain mordant[5] reflectivity, I recalled yesterday as the rain poured down from the sky these lines from Genesis:

5 When the Lord saw how great the wickedness of human beings was on earth, and how every desire that their heart conceived was always nothing but evil,c 6 the Lord regretted making human beings on the earth, and his heart was grieved.* [6]

These lines mark the opening of that great and timeless Tale of the Great Flood (Genesis 6-9).

If one is not careful – and we humans are often not careful – then we, reading these lines, will fix our attention on God’s harsh judgment about us humans … and overlook utterly that God has the capacity to feel hurt!

In our cussed[7] self-absorption, we conclude that God is judgmental[8] (and His judgment of us scares us; and we think it unfair) rather than noticing that this expression of His mighty heart’s hurt is itself a practice of vulnerability towards us.

Yet God’s “vulnerability”[9] (literally, God’s ability to be “hurt” by human beings) becomes a delicate matter when we human beings have, in our intemperance,[10] lost the ability to understand how the hurt Someone who is truly good feels in the face of our gross moral failure can clarify the unchanging steadfastness in goodness of the offended (divine) Person. In other words, God’s “vulnerability” biblically articulated reveals Who and how God really is. His unchanging goodness is made more obvious to us who are habitually changeable and sometimes content to be cussed.

Suffering, the suffering of a good person, is the furnace in which the essence of a person is refined; what really matters to him or her reveals itself. God’s “hurt” does not confuse or change Him; it reveals Him!

God’s “anger” implies no perturbation of the divine mind. It is simply the divine judgment passing sentence on sin. And when God “thinks and then has second thoughts,” this merely means that changeable realities come into relation with his immutable reason. For God cannot “repent,” as human beings repent, of what he has done, since in regard to everything his judgment is as fixed as his foreknowledge is clear. But it is only by the use of such human expressions that Scripture can make its many kinds of readers whom it wants to help to feel, as it were, at home. Only thus can Scripture frighten the proud and arouse the slothful, provoke inquiries and provide food for the convinced. This is possible only when Scripture gets right down to the level of the lowliest readers. City of God 15.25.5 [11]

Oh, Peregrinus, I need your example of careful thinking, because such a thing is so rare in our public life as Americans. Even when people appear to be offering reasons, they really are not. They, intemperately boiling with emotions too strong, imagine that their emotions are reasons, and so, are self-justifying!

My brother Bill put me in touch with the painting by Rembrandt that I have set at the head of this Letter. I wonder what you think about it. Here are four things that were catalyzed in me by a contemplation of that masterpiece.

I.

Rembrandt has us meet up with Moses probably in the first year (of what was to become forty years!) of the wandering of God’s people in the Wilderness. We find Moses descending Mount Sinai after having spent “forty days and nights” in a profound encounter with God.

I wondered about wandering, and so I started by making sure that I understood that verb:

This definition clarified for me that this people was not “wandering” between their release from Egypt and their arrival at Mount Sinai (Exodus 12-19). Moses knew exactly where he needed to bring this people – to Mount Sinai – to a place that he had been before, to the place where Moses first knew that God knew him, intimately, and who learned how aware God was of his kinsmen enslaved in Egypt (Exodus 3). If one knows where he is going, and how to get there, he (and those he leads) is not wandering; they are pilgrims (a pilgrim always knows the destination that he or she is towards).

This is why, Peregrinus (Latin for “pilgrim”), I love how you have lived into the meaning of your name. Your clarity about where we need to get to – into the making of a community, a community of WE, that causes to exist a common good “on earth, as it is in Heaven” – allows you to be more discerning and wise about how we get there. You taught me to see and to love the goal – what Jesus called “the reign of God” – so that loving the End with always greater devotion, I have the means to discern how to get us there … and to avoid what will not get us there.

So, from Egypt to Mount Sinai, the people of God were not wanderers but pilgrims. But it does become clear that after Mount Sinai – the great dissension that began (Exodus 32) as early as the giving of that extraordinary grace of a WE that included God – the people of God, even under Moses’ leadership, often fell back into wandering.

I wondered about wandering, and so I started by making sure that I understood that verb:

The Oxford English Dictionary at the verb “to wander” – “Of persons or animals: To move hither and thither without fixed course or certain aim; to be (in motion) without control or direction; to roam, ramble, go idly or restlessly about; to have no fixed abode or station.”

This definition clarified for me that this people was not “wandering” between their release from Egypt and their arrival at Mount Sinai (Exodus 12-19). Moses knew exactly where he needed to bring this people – to Mount Sinai – to a place that he had been before, to the place where Moses first knew that God knew him, intimately, and who learned how aware God was of his kinsmen enslaved in Egypt (Exodus 3). If one knows where he is going, and how to get there, he (and those he leads) is not wandering; they are pilgrims (a pilgrim always knows the destination that he or she is towards).

This is why, Peregrinus (Latin for “pilgrim”), I love how you have lived into the meaning of your name. Your clarity about where we need to get to – into the making of a community, a community of WE, that causes to exist a common good “on earth, as it is in Heaven” – allows you to be more discerning and wise about how we get there. You taught me to see and to love the goal – what Jesus called “the reign of God” – so that loving the End with always greater devotion, I have the means to discern how to get us there … and to avoid what will not get us there.

So, from Egypt to Mount Sinai, the people of God were not wanderers but pilgrims. But it does become clear that after Mount Sinai – the great dissension that began (Exodus 32) as early as the giving of that extraordinary grace of a WE that included God – the people of God, even under Moses’ leadership, often fell back into wandering.

II.

I recall reading in Exodus 24:12-18 that God called Moses (who is accompanied by “his assistant, Joshua”) to come to Him higher up on the mountain than the rest of the Israelites. God indicated that He wished to carve into stone what earlier God had spoken, person to person, to Moses (Exodus 20:1-17 – the “ten Commandments”).

What strikes me as significant is that God then chose to take the relationship that He had developed with Moses in person – interpersonally; voice to ear – and to carve a description of how that relationship worked onto stone tablets. Why did God do that? There is something dangerous that happens to Law when a people gets to thinking that the Law is something written, contained in books in legal libraries, imprinted on pages, rather than the Law as describing an experience of a particular kind of profound relationship, one person with another, which those involved in that relationship want to protect, and into which we want to invite others.[12] The Law is the relationship that it describes. Only in a secondary sense is the Law written in books and codified and studied … or gamed.

I hear in the opening lines of our national Constitution a commitment to a precious mutuality. This “We” that has remained one of the highest expressions of human hope in the world, and a wonder of the world that such a “We” became possible, let alone that it became firmly established as America.[13] Notice how the very first word expresses the precious intent of everything that follows: “WE”.

Peregrinus, you may ask why I appear to have lost touch with the story of Moses and God on Mount Sinai! Well, our troubled land has been so much on my mind and in my heart’s concern.

Yet, this that I have expressed about the “We”, the constitutional “We”, reveals something about why God was so angry with the Israelites (Exodus 32:7ff), and from which horrible anger Moses (remember that hurt always comes before anger in a healthy personality), with astonishing courage and boldness, talks God down (Exodus 32:11-14).[19] What God had done with and through Moses was to establish a divine “We” that was now to include this nationless people wandering with Moses in the Wilderness. The sheer majesty of this “We” that God established through Moses, the astonishing beauty of it, can at times be felt by us, and rightly, as “a glorious Mystery.” That the people so quickly threw that away must have stung.

What occurs to me, Peregrinus, and what has been challenging me again, is how we Americans have a lot of work to do on our “We”. And even when we imagine that we are doing it better than those others, the very fact of a THEM proves that we still do not understand what God did through Moses, or for that matter, what our national Constitution means.

What strikes me as significant is that God then chose to take the relationship that He had developed with Moses in person – interpersonally; voice to ear – and to carve a description of how that relationship worked onto stone tablets. Why did God do that? There is something dangerous that happens to Law when a people gets to thinking that the Law is something written, contained in books in legal libraries, imprinted on pages, rather than the Law as describing an experience of a particular kind of profound relationship, one person with another, which those involved in that relationship want to protect, and into which we want to invite others.[12] The Law is the relationship that it describes. Only in a secondary sense is the Law written in books and codified and studied … or gamed.

I hear in the opening lines of our national Constitution a commitment to a precious mutuality. This “We” that has remained one of the highest expressions of human hope in the world, and a wonder of the world that such a “We” became possible, let alone that it became firmly established as America.[13] Notice how the very first word expresses the precious intent of everything that follows: “WE”.

We the People[14] of the United States, in Order to[15] form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare,[16] and secure the Blessings of Liberty[17] to ourselves and our Posterity do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.[18]

Peregrinus, you may ask why I appear to have lost touch with the story of Moses and God on Mount Sinai! Well, our troubled land has been so much on my mind and in my heart’s concern.

Yet, this that I have expressed about the “We”, the constitutional “We”, reveals something about why God was so angry with the Israelites (Exodus 32:7ff), and from which horrible anger Moses (remember that hurt always comes before anger in a healthy personality), with astonishing courage and boldness, talks God down (Exodus 32:11-14).[19] What God had done with and through Moses was to establish a divine “We” that was now to include this nationless people wandering with Moses in the Wilderness. The sheer majesty of this “We” that God established through Moses, the astonishing beauty of it, can at times be felt by us, and rightly, as “a glorious Mystery.” That the people so quickly threw that away must have stung.

What occurs to me, Peregrinus, and what has been challenging me again, is how we Americans have a lot of work to do on our “We”. And even when we imagine that we are doing it better than those others, the very fact of a THEM proves that we still do not understand what God did through Moses, or for that matter, what our national Constitution means.

III.

Peregrinus, I have tried to understand the expression that Rembrandt has captured on the face of Moses. His face is the brightest thing in the painting.[20]

That beautiful face expresses hurt and, I think, deep weariness in the complicated work of leadership. Rembrandt has painted Moses at the moment when he saw what his own brother, Aaron,[21] had done, how Aaron had misled the people while he, Moses, was up high on the mountain with God. It was his brother who had been the source of the idea of melting down gold jewelry and turning it into a god-image - a golden calf – for the people to worship. The hurt is eloquent on Moses’ face. It hurts me to look on that face.

I feel such admiration for the man that Moses became walking with God, who could and did feel hurt. He allows us to see his vulnerability (so glad that Rembrandt was there!), the hurt expressing the complex grace that he felt as a profound lover of God and a man with a deep devotion to God’s people, among whose number he stood. He clings to both loves. (A bad leader will always love his or her patrons or sponsors (or sycophants) more than the “We” that he or she is given to lead.)

It is at this precise moment – at the clashing of his two great loves – that we see why Moses was so great a leader of people. As wounded as both loves had left him, still, he holds high above him, in those gentle hands, the one thing that will secure the unity of those two loves – the “We” for the sake of which he has given his life!

I think of another wounded man, a truly great leader, a servant of two great loves – his love of God and his love for the badly wounded “We” of America[23] – who said with typical eloquence, and with a face that must have looked an awful lot like that of Moses in the painting:

With malice toward none with charity for all with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan ~ to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.[24]

That beautiful face expresses hurt and, I think, deep weariness in the complicated work of leadership. Rembrandt has painted Moses at the moment when he saw what his own brother, Aaron,[21] had done, how Aaron had misled the people while he, Moses, was up high on the mountain with God. It was his brother who had been the source of the idea of melting down gold jewelry and turning it into a god-image - a golden calf – for the people to worship. The hurt is eloquent on Moses’ face. It hurts me to look on that face.

I feel such admiration for the man that Moses became walking with God, who could and did feel hurt. He allows us to see his vulnerability (so glad that Rembrandt was there!), the hurt expressing the complex grace that he felt as a profound lover of God and a man with a deep devotion to God’s people, among whose number he stood. He clings to both loves. (A bad leader will always love his or her patrons or sponsors (or sycophants) more than the “We” that he or she is given to lead.)

It is at this precise moment – at the clashing of his two great loves – that we see why Moses was so great a leader of people. As wounded as both loves had left him, still, he holds high above him, in those gentle hands, the one thing that will secure the unity of those two loves – the “We” for the sake of which he has given his life!

15 Moses then turned and came down the mountain with the two tablets of the covenant in his hands,h tablets that were written on both sides, front and back. 16 The tablets were made by God; the writing was the writing of God, engraved on the tablets.i [22]

I think of another wounded man, a truly great leader, a servant of two great loves – his love of God and his love for the badly wounded “We” of America[23] – who said with typical eloquence, and with a face that must have looked an awful lot like that of Moses in the painting:

With malice toward none with charity for all with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan ~ to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.[24]

IV.

Last of all, old friend, I found myself understanding suddenly the origin (it must be) of the phrase “to break the Law.” It must have its source with Moses!

But to conclude correctly as to why Moses broke the tablets is of great importance. Notice that Moses broke both artifacts involved! He shattered the stone Tablets and the Golden Calf.

Perhaps Moses knew that whenever we transfer a living relationship that matters into a physical object (a church building, a governmental building, a monument, a pile of money, etc.), and then begin to relate to that physical object as if it were the relationship, we put a living relationship in danger of breaking.[26]

Perhaps Moses had had quite enough of “objects” or “artifacts” – enough of honoring them; holding on to them. Now was the time, he concluded, for them to do the hard work of relationship with the actual persons involved, for God’s people to learn how to love each another, to love in the way the Ten Commandments instructed, and then through long practice (the meaning of the “forty years” in the Wilderness) to become the WE that God expected them to establish.

Well, Peregrinus, I leave you for now, expressing my admiration for the leader that Moses was, someone for whom Jesus had greatest esteem (especially as Moses is portrayed in the Book of Deuteronomy).

I also remember you with admiration, old friend. And to be frank about it, I miss you.

Love,

Rick

19 As he drew near the camp, he saw the calf and the dancing. Then Moses’ anger burned, and he threw the tablets down and broke them on the base of the mountain.j[25]

But to conclude correctly as to why Moses broke the tablets is of great importance. Notice that Moses broke both artifacts involved! He shattered the stone Tablets and the Golden Calf.

Perhaps Moses knew that whenever we transfer a living relationship that matters into a physical object (a church building, a governmental building, a monument, a pile of money, etc.), and then begin to relate to that physical object as if it were the relationship, we put a living relationship in danger of breaking.[26]

Perhaps Moses had had quite enough of “objects” or “artifacts” – enough of honoring them; holding on to them. Now was the time, he concluded, for them to do the hard work of relationship with the actual persons involved, for God’s people to learn how to love each another, to love in the way the Ten Commandments instructed, and then through long practice (the meaning of the “forty years” in the Wilderness) to become the WE that God expected them to establish.

Well, Peregrinus, I leave you for now, expressing my admiration for the leader that Moses was, someone for whom Jesus had greatest esteem (especially as Moses is portrayed in the Book of Deuteronomy).

I also remember you with admiration, old friend. And to be frank about it, I miss you.

Love,

Rick

Notes

[1] A colloquial form of “ordinary”. The Oxford English Dictionary at “ornery” – “commonplace, inferior, unpleasant; (now) esp. mean, cantankerous, contrary.”

[2] The last stanza/verse of “I Wonder as I Wander” – Wikipedia - "I Wonder as I Wander" is a Christian folk hymn, typically performed as a Christmas carol, written by American folklorist and singer John Jacob Niles. The hymn has its origins in a song fragment collected by Niles on July 16, 1933. It was first performed on 19 December 1933.”

[3] Wikipedia – “John R. Cash (born J. R. Cash; February 26, 1932 – September 12, 2003) was an American singer, songwriter, musician, and actor. Much of Cash's music contained themes of sorrow, moral tribulation, and redemption, especially in the later stages of his career. He was known for his deep, calm bass-baritone voice, the distinctive sound of his Tennessee Three backing band characterized by train-like chugging guitar rhythms, a rebelliousness coupled with an increasingly somber and humble demeanor, free prison concerts, and a trademark all-black stage wardrobe which earned him the nickname ‘The Man in Black’.”

[4] Hilary of Poitiers, St (c. 315–67/8), the ‘Athanasius of the West’. An educated convert from paganism, he was elected Bp. of Poitiers c. 350 and subsequently became involved in the *Arian disputes. His condemnation at the Synod of Biterrae (356) is usually attributed to his defence of Catholic teaching, but some scholars have suggested that other factors may initially have been involved. It was followed by a four-year exile to Phrygia by the Emp. Constantius, whom Hilary later denounced as *Antichrist. In 359 he defended the cause of orthodoxy at the Council of *Seleucia, and he became the leading and most respected Latin theologian of his age. [F. L. Cross and Elizabeth A. Livingstone, eds., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 774.]

[5] The Oxford English Dictionary at the adjective “mordant” – “Of a person, his or her wit, a remark, etc.: having or showing a sharply critical quality; biting, caustic, incisive.”

c Ps 14:2–3.

* His heart was grieved: the expression can be misleading in English, for “heart” in Hebrew is the seat of memory and judgment rather than emotion. The phrase is actually parallel to the first half of the sentence (“the Lord regretted …”).

[6] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ge 6:5–6.

[7] “cussed” – I have felt growing alarm, and for some years now, when I see people confusing “steadfastness” of character (a really good quality in a person) with cussedness. The Oxford English Dictionary at “cussed” – “Obstinate or stubborn, esp. to the point of causing annoyance or frustration; cantankerous, contrary.” And because we drift into this confusion about the truth, we make ourselves enormously available to assume that persons are strong and impressive, who are in fact habitually “obstinate, cantankerous, contrary” (signs of a blighted character).

[8] “judgmental” – God cannot be judgmental. Why? If I am “judgmental,” then that means that I decide about the truth of someone as it relates to me, to my tribe, or to my interest group (church or nation or business, etc.). In contrast, for me to exercise or to have “good judgment” means that I affirm the truth of someone in his or her otherness from me, on his or her own ground, and within the wider context in which he or she dwells. To be judgmental makes the “truth” all about me; I am the center of my universe. By contrast, if I have good judgment, then I affirm the otherness of the other no matter what I desire him or her to be, whether they help or hurt me, whether I like having them exist at all! God has no capacity to be judgmental. It is a projection onto God of our own internal disorders to affirm, even to suspect, that God is judgmental.

[9] “vulnerable” – The Oxford English Dictionary at “vulnerable” – “figurative. Open to attack or injury of a non-physical nature; esp., offering an opening to the attacks of raillery, criticism, calumny, etc.”

[10] “intemperance” – The Oxford English Dictionary at “intemperance” – “Lack of moderation or restraint; excess in any kind of action; immoderation; spec. excessive indulgence of any passion or appetite.” An “intemperate” person is one who has been taken over by his or her emotions, whose affective life at a foundational level has been poisoned by “bad thoughts” (for the significance of “bad thoughts” in the spiritual life see Evagrius of Pontus, as one particularly famous example of this teaching of the Desert Tradition of Christianity) and inflamed and made susceptible to easy manipulation by the Unnamed Powers (by evil). As to Evagrius, see Wikipedia: “Evagrius Ponticus (Greek: Εὐάγριος ὁ Ποντικός, "Evagrius of Pontus"; also called Evagrius the Solitary (345–399 AD), was a Christian monk and ascetic. One of the most influential theologians in the late fourth-century church, he was well known as a thinker, polished speaker, and gifted writer.”

*5 FC 14:476–77.

[11] Andrew Louth and Marco Conti, eds., Genesis 1–11, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2001), 127–128.

[12] “we want to invite others” – It is a sign of a mature friendship, one grounded in goodness, that it wants to bring others into it. A mature friendship delights to share his or her friend (or nation) with others; an immature friendship wants to remain exclusive – “My precious!” as Gollum so famously hisses.

[13] All of the words of, say, the US Constitution are the right ones, wondrous and important words. However, we all know too well how much that Constitutional “We” excluded people in this land who had just as much right to that “We” as any of us did. We have much to repent. We have been forced to acknowledge an “inconvenient truth” about this “city on the hill”. But the hope and the possibility of “a more perfect Union” (a larger “We”, which heals the smaller “We” and teaches it to be better) shines brightly in those noble words. Perhaps it should have said, rather than “a more perfect Union”, a “more humble, grateful Union.” But then, maybe that is what that adjective “perfect” meant!

[14] Not, “I, Trump”; not “We the Democrats or Republicans or Proud Boys or Evangelicals or Catholics or Jews or LGBTQ+ or the Young, or the Older.” It is WE, a messy mix of all kinds of people, good and bad alike, all of whom have deep within them each a longing to be significant, or better, to know that they have found their gift and have fully given it, without measure, for the common good, and to the glory of God whose world this is. There is such grandeur, and bold hoping, in those opening three words: “We the people”, especially when we see how often certain people, those who judge themselves more important than other people, claim ownership for themselves of the “We”. As long as the “We” is secured, taken as a rock-solid and essential principle, there can be no THEM.

[15] “in order to” – This is a Purpose Clause, which expresses the good that we all seek together: to take the unity that we have received as a blessing – “the Blessings of Liberty”, and by an enormous effort of careful thought, high-mindedness, and savvy, to put into place a structure – a government – that protects and defends, but also defines, the preciousness of what we have already felt together and to make it better than it is, “to form a more perfect unity.”

[16] “the general Welfare” – In this case “general” does not mean vague or unfocused (as we might say that something is “generally” true). It establishes the priority of the general over the particular. The “general Welfare” is what we mean when we speak of “the common good.” In other words, the common good must be foremost when we act governmentally, lest the good of the few will, lacking restraint, simply hijack the good for themselves first, and keep it that way.

[17] “to secure the Blessings” – How often now in our political and conversational expression mean by “to secure” something to do with law enforcement or the military. We say, “to secure the border” or “Homeland Security”, and so forth. Why is it that we never hear about the Blessings, about the “Blessings of Liberty”?

[18] For example: https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/full-text.

[19] God’s expression of deep hurt, and then of wrath, as recorded here in this text from Exodus 32, shows a revealing likeness to what Jesus would reference in what is perhaps His most famous parable: the story of the Prodigal, of the elder Brother, and of the Father in Luke 15. Notice how God in His wrath says to Moses: “Go down at once! Your people, whom you brought up out of the land of Egypt….” (Exodus 32:7) This sounds exactly like the elder Brother who speaks angrily to his dad, “This son of yours…”, rather than saying “My brother….” And then notice how Moses, when he begins to remonstrate with God (!) says: “O Lord, why does your wrath burn hot against your people, whom You [not me!] brought out of the land of Egypt with great power and with a mighty hand?” Recall what the father of Luke 15 will say to his angry elder son: “because this brother of yours was dead and has come back to life; he was lost and has been found” (Luke 15:32).

[20] There is a tradition that Moses’ face became bright with divine Light after his long conversations with God, face to face. But that is not the case in this earlier stage in their relationship.

[21] Actually there is a great deal of argument about the siblings of Moses, as there has been about the “siblings” of Jesus. See, for example: https://www.thetorah.com/article/moses-aaron-and-miriam-were-they-siblings.

h Dt 9:15.

i Ex 31:18.

[22] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ex 32:15–16.

[23] I heard a commentator recently who spoke of racism in America, especially against Blacks, as a “birth defect” clinging to America at its birth. It is a fascinating way to speak of it, though, subtly, it could give us Americans a way of denying responsibility for it. No one deliberately desires that his or her child be born with a birth defect; it just happens.

[24] The closing lines of Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, given on 4 March 1865, just forty-one days before he was assassinated. See: https://www.nps.gov/linc/learn/historyculture/lincoln-second-inaugural.htm.

j Dt 9:16–17.

[25] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ex 32:19.

[26] One of the more malignant cultural developments in America has been what we have seen happen around “Christmas shopping”, where it has everything to do with “shopping” and nothing remotely to do with “Christmas.” Have you noticed, as I have, how often now the married relationship is being overtly associated with a spouse purchasing for his or her beloved an enormously expensive physical object: an expensive piece of jewelry; a way too expensive automobile, etc.? That physical object is meant to “stand for” a married relationship of exceptional quality. Oh dear.

[2] The last stanza/verse of “I Wonder as I Wander” – Wikipedia - "I Wonder as I Wander" is a Christian folk hymn, typically performed as a Christmas carol, written by American folklorist and singer John Jacob Niles. The hymn has its origins in a song fragment collected by Niles on July 16, 1933. It was first performed on 19 December 1933.”

[3] Wikipedia – “John R. Cash (born J. R. Cash; February 26, 1932 – September 12, 2003) was an American singer, songwriter, musician, and actor. Much of Cash's music contained themes of sorrow, moral tribulation, and redemption, especially in the later stages of his career. He was known for his deep, calm bass-baritone voice, the distinctive sound of his Tennessee Three backing band characterized by train-like chugging guitar rhythms, a rebelliousness coupled with an increasingly somber and humble demeanor, free prison concerts, and a trademark all-black stage wardrobe which earned him the nickname ‘The Man in Black’.”

[4] Hilary of Poitiers, St (c. 315–67/8), the ‘Athanasius of the West’. An educated convert from paganism, he was elected Bp. of Poitiers c. 350 and subsequently became involved in the *Arian disputes. His condemnation at the Synod of Biterrae (356) is usually attributed to his defence of Catholic teaching, but some scholars have suggested that other factors may initially have been involved. It was followed by a four-year exile to Phrygia by the Emp. Constantius, whom Hilary later denounced as *Antichrist. In 359 he defended the cause of orthodoxy at the Council of *Seleucia, and he became the leading and most respected Latin theologian of his age. [F. L. Cross and Elizabeth A. Livingstone, eds., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 774.]

[5] The Oxford English Dictionary at the adjective “mordant” – “Of a person, his or her wit, a remark, etc.: having or showing a sharply critical quality; biting, caustic, incisive.”

c Ps 14:2–3.

* His heart was grieved: the expression can be misleading in English, for “heart” in Hebrew is the seat of memory and judgment rather than emotion. The phrase is actually parallel to the first half of the sentence (“the Lord regretted …”).

[6] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ge 6:5–6.

[7] “cussed” – I have felt growing alarm, and for some years now, when I see people confusing “steadfastness” of character (a really good quality in a person) with cussedness. The Oxford English Dictionary at “cussed” – “Obstinate or stubborn, esp. to the point of causing annoyance or frustration; cantankerous, contrary.” And because we drift into this confusion about the truth, we make ourselves enormously available to assume that persons are strong and impressive, who are in fact habitually “obstinate, cantankerous, contrary” (signs of a blighted character).

[8] “judgmental” – God cannot be judgmental. Why? If I am “judgmental,” then that means that I decide about the truth of someone as it relates to me, to my tribe, or to my interest group (church or nation or business, etc.). In contrast, for me to exercise or to have “good judgment” means that I affirm the truth of someone in his or her otherness from me, on his or her own ground, and within the wider context in which he or she dwells. To be judgmental makes the “truth” all about me; I am the center of my universe. By contrast, if I have good judgment, then I affirm the otherness of the other no matter what I desire him or her to be, whether they help or hurt me, whether I like having them exist at all! God has no capacity to be judgmental. It is a projection onto God of our own internal disorders to affirm, even to suspect, that God is judgmental.

[9] “vulnerable” – The Oxford English Dictionary at “vulnerable” – “figurative. Open to attack or injury of a non-physical nature; esp., offering an opening to the attacks of raillery, criticism, calumny, etc.”

[10] “intemperance” – The Oxford English Dictionary at “intemperance” – “Lack of moderation or restraint; excess in any kind of action; immoderation; spec. excessive indulgence of any passion or appetite.” An “intemperate” person is one who has been taken over by his or her emotions, whose affective life at a foundational level has been poisoned by “bad thoughts” (for the significance of “bad thoughts” in the spiritual life see Evagrius of Pontus, as one particularly famous example of this teaching of the Desert Tradition of Christianity) and inflamed and made susceptible to easy manipulation by the Unnamed Powers (by evil). As to Evagrius, see Wikipedia: “Evagrius Ponticus (Greek: Εὐάγριος ὁ Ποντικός, "Evagrius of Pontus"; also called Evagrius the Solitary (345–399 AD), was a Christian monk and ascetic. One of the most influential theologians in the late fourth-century church, he was well known as a thinker, polished speaker, and gifted writer.”

*5 FC 14:476–77.

[11] Andrew Louth and Marco Conti, eds., Genesis 1–11, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2001), 127–128.

[12] “we want to invite others” – It is a sign of a mature friendship, one grounded in goodness, that it wants to bring others into it. A mature friendship delights to share his or her friend (or nation) with others; an immature friendship wants to remain exclusive – “My precious!” as Gollum so famously hisses.

[13] All of the words of, say, the US Constitution are the right ones, wondrous and important words. However, we all know too well how much that Constitutional “We” excluded people in this land who had just as much right to that “We” as any of us did. We have much to repent. We have been forced to acknowledge an “inconvenient truth” about this “city on the hill”. But the hope and the possibility of “a more perfect Union” (a larger “We”, which heals the smaller “We” and teaches it to be better) shines brightly in those noble words. Perhaps it should have said, rather than “a more perfect Union”, a “more humble, grateful Union.” But then, maybe that is what that adjective “perfect” meant!

[14] Not, “I, Trump”; not “We the Democrats or Republicans or Proud Boys or Evangelicals or Catholics or Jews or LGBTQ+ or the Young, or the Older.” It is WE, a messy mix of all kinds of people, good and bad alike, all of whom have deep within them each a longing to be significant, or better, to know that they have found their gift and have fully given it, without measure, for the common good, and to the glory of God whose world this is. There is such grandeur, and bold hoping, in those opening three words: “We the people”, especially when we see how often certain people, those who judge themselves more important than other people, claim ownership for themselves of the “We”. As long as the “We” is secured, taken as a rock-solid and essential principle, there can be no THEM.

[15] “in order to” – This is a Purpose Clause, which expresses the good that we all seek together: to take the unity that we have received as a blessing – “the Blessings of Liberty”, and by an enormous effort of careful thought, high-mindedness, and savvy, to put into place a structure – a government – that protects and defends, but also defines, the preciousness of what we have already felt together and to make it better than it is, “to form a more perfect unity.”

[16] “the general Welfare” – In this case “general” does not mean vague or unfocused (as we might say that something is “generally” true). It establishes the priority of the general over the particular. The “general Welfare” is what we mean when we speak of “the common good.” In other words, the common good must be foremost when we act governmentally, lest the good of the few will, lacking restraint, simply hijack the good for themselves first, and keep it that way.

[17] “to secure the Blessings” – How often now in our political and conversational expression mean by “to secure” something to do with law enforcement or the military. We say, “to secure the border” or “Homeland Security”, and so forth. Why is it that we never hear about the Blessings, about the “Blessings of Liberty”?

[18] For example: https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/full-text.

[19] God’s expression of deep hurt, and then of wrath, as recorded here in this text from Exodus 32, shows a revealing likeness to what Jesus would reference in what is perhaps His most famous parable: the story of the Prodigal, of the elder Brother, and of the Father in Luke 15. Notice how God in His wrath says to Moses: “Go down at once! Your people, whom you brought up out of the land of Egypt….” (Exodus 32:7) This sounds exactly like the elder Brother who speaks angrily to his dad, “This son of yours…”, rather than saying “My brother….” And then notice how Moses, when he begins to remonstrate with God (!) says: “O Lord, why does your wrath burn hot against your people, whom You [not me!] brought out of the land of Egypt with great power and with a mighty hand?” Recall what the father of Luke 15 will say to his angry elder son: “because this brother of yours was dead and has come back to life; he was lost and has been found” (Luke 15:32).

[20] There is a tradition that Moses’ face became bright with divine Light after his long conversations with God, face to face. But that is not the case in this earlier stage in their relationship.

[21] Actually there is a great deal of argument about the siblings of Moses, as there has been about the “siblings” of Jesus. See, for example: https://www.thetorah.com/article/moses-aaron-and-miriam-were-they-siblings.

h Dt 9:15.

i Ex 31:18.

[22] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ex 32:15–16.

[23] I heard a commentator recently who spoke of racism in America, especially against Blacks, as a “birth defect” clinging to America at its birth. It is a fascinating way to speak of it, though, subtly, it could give us Americans a way of denying responsibility for it. No one deliberately desires that his or her child be born with a birth defect; it just happens.

[24] The closing lines of Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, given on 4 March 1865, just forty-one days before he was assassinated. See: https://www.nps.gov/linc/learn/historyculture/lincoln-second-inaugural.htm.

j Dt 9:16–17.

[25] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ex 32:19.

[26] One of the more malignant cultural developments in America has been what we have seen happen around “Christmas shopping”, where it has everything to do with “shopping” and nothing remotely to do with “Christmas.” Have you noticed, as I have, how often now the married relationship is being overtly associated with a spouse purchasing for his or her beloved an enormously expensive physical object: an expensive piece of jewelry; a way too expensive automobile, etc.? That physical object is meant to “stand for” a married relationship of exceptional quality. Oh dear.

Recent

Categories

Tags

Archive

2026

2025

January

March

June

October

2024

January

March

September

October

2023

March

November

2022

2021

2020

No Comments