Letters to Peregrinus #52 - On Kindness

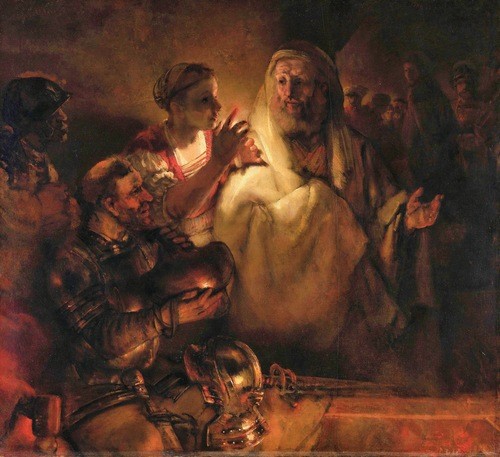

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (c. 1606-1669)[1] – The Denial of Saint Peter (1660)[2]

in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rembrandt_Harmensz._van_Rijn_012.jpg

in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rembrandt_Harmensz._van_Rijn_012.jpg

W. H. Auden’s [1907-1973] “Forward” to Owen Barfield’s [1898-1997] book, History in English Words – “To-day we must modify Mr. Barfield's warning and say that nine-tenths of the population use twice as many words as they understand. It is no longer a matter of their knowing some of the possible meanings of the words they use; they attach meanings to them which are simply false.”[3]

William Stafford (1914-1993), written on a standing-stone in Foothills Park, Lake Oswego: “The stream is always revising / water is always ready to learn.”

Charlie Mackesy[4] called The Boy, the Mole the Fox, and the Horse[5] - Mole asking the boy, his new friend, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” The boy replies, “Kind.”[6]

Dear Peregrinus (Tuesday, the Birth of Mary of Nazareth[7]):

How quickly we have been vaulted into September, but how hard to grasp that this is true, because there are no school buses out in traffic. At this time of year, the roads would normally be clogged, in part because of the thousands of newly licensed teens driving themselves, and their younger siblings, to school. I can still feel in my hands, at 66-years old, that buzzing in the steering wheel of the “kids’ car”, of our green, four-wheel drive International Scout, when I drove to Gonzaga Prep for the first time in September of 1968. I can still feel the thrill of it.

With admiration I salute you, old friend, who chose in this Age of COVID, to invest your home-time re-reading the classic literature of your youth, falling again under the spell of those books that enchanted you in those days, when reading was for you and your parents and siblings a primary mode of recreation each day.

Look with me at that painting by Rembrandt (above), the artist’s contemplation of Luke 22:54-62, the only account that records that Jesus “turned and looked at Peter”[8] –

And as you contemplate the fruit of Rembrandt’s contemplation of Peter and Jesus and of the others placed there by the artist inside the frame, tell me, when you get a chance to write me back, what you consider the most compelling aspect of his painting.

Here, I offer you three points that captured my attention.

First, Rembrandt was a master of the chiaroscuro style or technique.[10]

What strikes me is how Rembrandt appears to begin his composition with “darkness” – as if he had first painted the white canvas black (or light-less), as if imitating what God saw of the uncreated world on that first day when He began to create the universe.

Rembrandt in imitation of God’s own masterwork (the Universe!) then “spoke” through his paintbrushes: “Let there be light”! We who could not see in the dark (the darkened nature of our spiritual understanding of the Scriptures) are given the ability to find therein a sacred drama happening in the life of Peter, and in the life of Jesus Who “turns”. It is as if Rembrandt paints with light (not with paint), opening our minds (as well as our eyes) to insight, to real spiritual understanding of this biblical scene. I recall what St. Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 13:

Second, the biblical text explicitly says that Jesus “turned”, looking toward Peter. But in the biblical world, “turning” – to be converted - is regularly associated with a work of sinful humanity, whom the Prophets and then Jesus Himself continually enjoined[14] to “turn away from sin and believe in the Gospel”, as the Ash Wednesday language has it. The Oxford English Dictionary at the noun “conversion”[15] (from the Latin conversio) defines it: “the action of turning around, or in a particular direction”. But theologically, “conversion” means: “The turning of sinners to God; a spiritual change from sinfulness, ungodliness, or worldliness to love of God and pursuit of holiness.” Conversion and repentance are closely linked in the great Religions.

But, is it possible that Rembrandt understood, where we missed it, a divine humility so remarkable that the real significance of this scene is that it is not about Peter, but about something that happened in the Christ?[16] Was it that Jesus the Christ accepted that evening a profound deepening of His own understanding of the broken heart of his close friend – a conversion in His way of seeing Peter,[17] an adjustment of His expectations of him? Such a conversion in Jesus includes of course, as real conversion in us often includes, His acceptance of the breaking of His own heart.

Peregrinus, I believe that Rembrandt perceived a conversion, there and at that moment, in Christ’s understanding of human brokenness – it is his own dear Peter, his “rock”! - and the depth of our human need for divine help. If one of His closest friends, whom He knew loved Him, could betray Him so completely, then how likely it was that anyone had that capacity in his or her heart?[19] Perhaps, Rembrandt understood that Jesus needed to see this, and right then, just as the great work – the Paschal Mystery - had now entered its most intense phase.

I am thinking so. Rembrandt is revealing to us the profound kindness of God far more than he is wondering about the betrayal of Peter. (Why do we human beings always want to make our sinfulness the most important thing?) Perhaps the proper title for this Gospel scene, recorded in all four Gospels, is: The Deepening of the Compassionate Insight of the Christ, or, The Breaking of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, or some such.

Third, it strikes me that the face of Peter is a face that could only look like that – the deep kindness of that face, and its vulnerability – after some great experience of lovingkindness[20] having been shown him by God, not before.

That face we see is not that of a man actively in the act of lying, of betraying a friend. Rembrandt, I believe, has painted the face of Peter as an old man, who in his imagination is looking back, contemplatively, and in light of the Resurrection, to the moment when his self-disappointment, his failure, was greatest. How often in his life he must have “found” himself going there in his memory! (In this regard, I completely disagree with even the experts who see betrayal and lies on Peter’s face in this painting. No way is that face about that.)

Therefore, Rembrandt’s point, I suggest, is that we each must learn to contemplate the story of our life in light of the Resurrection – in light of what the Father has already done in the Son through the power of the Holy Spirit for each of us.

Nearly everyone I know, and too often including me, contemplate the story of his or her life as if the Resurrection and Ascension had not yet happened … at least not for us. Rembrandt has painted Peter’s face as an old man, not at that moment, years earlier, when he was younger and had found himself in the courtyard of the palace of the High Priest. He paints that face as if to “say” on its surface, in every wrinkle and subtle expression, what St. Paul meant when he wrote these words to Timothy, what took him, and St. Peter, so many years to comprehend and to own!

Saint Paul’s face when dictating or writing these words must have looked very much like the face of Saint Peter in Rembrandt’s painting.

Let me know what you see, my old and trustworthy friend of so many adventures. You still can startle me with your capacity to see what I have overlooked. Thank you for the years.

Love,

Rick

How quickly we have been vaulted into September, but how hard to grasp that this is true, because there are no school buses out in traffic. At this time of year, the roads would normally be clogged, in part because of the thousands of newly licensed teens driving themselves, and their younger siblings, to school. I can still feel in my hands, at 66-years old, that buzzing in the steering wheel of the “kids’ car”, of our green, four-wheel drive International Scout, when I drove to Gonzaga Prep for the first time in September of 1968. I can still feel the thrill of it.

With admiration I salute you, old friend, who chose in this Age of COVID, to invest your home-time re-reading the classic literature of your youth, falling again under the spell of those books that enchanted you in those days, when reading was for you and your parents and siblings a primary mode of recreation each day.

C.S. Lewis in “Lilies that Fester” found in The World’s Last Night (1960) – “A live dog is better than a dead lion. In the same way, after a certain kind of sherry party, where there have been cataracts of culture but never one word or one glance that suggested a real enjoyment of any art, any person, or any natural object, my heart warms to the schoolboy on the bus who is reading Fantasy and Science Fiction, rapt and oblivious of all the world beside. For here also I should feel that I had met something real and live and unfabricated; genuine literary experience, spontaneous and compulsive, disinterested. I should have hopes of that boy. Those who have greatly cared for any book whatever may possibly come to care, someday, for good books. The organs of appreciation exist in them. They are not impotent.”

Look with me at that painting by Rembrandt (above), the artist’s contemplation of Luke 22:54-62, the only account that records that Jesus “turned and looked at Peter”[8] –

59 About an hour later, still another insisted, “Assuredly, this man too was with him, for he also is a Galilean.” 60 But Peter said, “My friend, I do not know what you are talking about.” Just as he was saying this, the cock crowed, 61 and the Lord turned and looked at Peter; and Peter remembered the word of the Lord, how he had said to him, “Before the cock crows today, you will deny me three times.” 62 He went out and began to weep bitterly.[9]

And as you contemplate the fruit of Rembrandt’s contemplation of Peter and Jesus and of the others placed there by the artist inside the frame, tell me, when you get a chance to write me back, what you consider the most compelling aspect of his painting.

Here, I offer you three points that captured my attention.

First, Rembrandt was a master of the chiaroscuro style or technique.[10]

It would be entirely wrong to reduce all Rembrandt’s work, in spiritual content as well as practical treatment, to the exploitation of chiaroscuro. However, throughout his life’s work, he used this strategy to raise the emotional level of his work, as a symbol of the contrast between light and dark, as a vehicle for his personal thoughts about the human condition, the terrestrial world, and biblical revelation.[11]

What strikes me is how Rembrandt appears to begin his composition with “darkness” – as if he had first painted the white canvas black (or light-less), as if imitating what God saw of the uncreated world on that first day when He began to create the universe.

Genesis 1 – 1 In the beginning, when God created the heavens and the earth—2 and the earth was without form or shape, with darkness over the abyss and a mighty wind sweeping over the waters - 3 Then God said: Let there be light, and there was light. 4 God saw that the light was good. God then separated the light from the darkness. 5 God called the light “day,” and the darkness he called “night.”[12]

Rembrandt in imitation of God’s own masterwork (the Universe!) then “spoke” through his paintbrushes: “Let there be light”! We who could not see in the dark (the darkened nature of our spiritual understanding of the Scriptures) are given the ability to find therein a sacred drama happening in the life of Peter, and in the life of Jesus Who “turns”. It is as if Rembrandt paints with light (not with paint), opening our minds (as well as our eyes) to insight, to real spiritual understanding of this biblical scene. I recall what St. Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 13:

12 We don’t yet see things clearly. We’re squinting in a fog, peering through a mist. But it won’t be long before the weather clears, and the sun shines bright! We’ll see it all then, see it all as clearly as God sees us, knowing him directly just as he knows us! 13 But for right now, until that completeness, we have three things to do to lead us toward that consummation: Trust steadily in God, hope unswervingly, love extravagantly. And the best of the three is love.[13]

Second, the biblical text explicitly says that Jesus “turned”, looking toward Peter. But in the biblical world, “turning” – to be converted - is regularly associated with a work of sinful humanity, whom the Prophets and then Jesus Himself continually enjoined[14] to “turn away from sin and believe in the Gospel”, as the Ash Wednesday language has it. The Oxford English Dictionary at the noun “conversion”[15] (from the Latin conversio) defines it: “the action of turning around, or in a particular direction”. But theologically, “conversion” means: “The turning of sinners to God; a spiritual change from sinfulness, ungodliness, or worldliness to love of God and pursuit of holiness.” Conversion and repentance are closely linked in the great Religions.

But, is it possible that Rembrandt understood, where we missed it, a divine humility so remarkable that the real significance of this scene is that it is not about Peter, but about something that happened in the Christ?[16] Was it that Jesus the Christ accepted that evening a profound deepening of His own understanding of the broken heart of his close friend – a conversion in His way of seeing Peter,[17] an adjustment of His expectations of him? Such a conversion in Jesus includes of course, as real conversion in us often includes, His acceptance of the breaking of His own heart.

Hosea 11 –

My heart is overwhelmed,

my pity is stirred.

9 I will not give vent to my blazing anger,

I will not destroy Ephraim again;

For I am God and not a man,g

the Holy One present among you;

I will not come in wrath. [18]

Peregrinus, I believe that Rembrandt perceived a conversion, there and at that moment, in Christ’s understanding of human brokenness – it is his own dear Peter, his “rock”! - and the depth of our human need for divine help. If one of His closest friends, whom He knew loved Him, could betray Him so completely, then how likely it was that anyone had that capacity in his or her heart?[19] Perhaps, Rembrandt understood that Jesus needed to see this, and right then, just as the great work – the Paschal Mystery - had now entered its most intense phase.

I am thinking so. Rembrandt is revealing to us the profound kindness of God far more than he is wondering about the betrayal of Peter. (Why do we human beings always want to make our sinfulness the most important thing?) Perhaps the proper title for this Gospel scene, recorded in all four Gospels, is: The Deepening of the Compassionate Insight of the Christ, or, The Breaking of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, or some such.

Third, it strikes me that the face of Peter is a face that could only look like that – the deep kindness of that face, and its vulnerability – after some great experience of lovingkindness[20] having been shown him by God, not before.

That face we see is not that of a man actively in the act of lying, of betraying a friend. Rembrandt, I believe, has painted the face of Peter as an old man, who in his imagination is looking back, contemplatively, and in light of the Resurrection, to the moment when his self-disappointment, his failure, was greatest. How often in his life he must have “found” himself going there in his memory! (In this regard, I completely disagree with even the experts who see betrayal and lies on Peter’s face in this painting. No way is that face about that.)

Therefore, Rembrandt’s point, I suggest, is that we each must learn to contemplate the story of our life in light of the Resurrection – in light of what the Father has already done in the Son through the power of the Holy Spirit for each of us.

Nearly everyone I know, and too often including me, contemplate the story of his or her life as if the Resurrection and Ascension had not yet happened … at least not for us. Rembrandt has painted Peter’s face as an old man, not at that moment, years earlier, when he was younger and had found himself in the courtyard of the palace of the High Priest. He paints that face as if to “say” on its surface, in every wrinkle and subtle expression, what St. Paul meant when he wrote these words to Timothy, what took him, and St. Peter, so many years to comprehend and to own!

12 I am grateful to him who has strengthened me, Christ Jesus our Lord, because he considered me trustworthy in appointing me to the ministry. 13 I was once a blasphemer and a persecutor and an arrogant man, but I have been mercifully treated because I acted out of ignorance in my unbelief. 14 Indeed, the grace of our Lord has been abundant, along with the faith and love that are in Christ Jesus. 15 This saying is trustworthy* and deserves full acceptance: Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners. Of these I am the foremost.m 16 But for that reason I was mercifully treated, so that in me, as the foremost, Christ Jesus might display all his patience as an example for those who would come to believe in him for everlasting life. 17 To the king of ages, incorruptible, invisible, the only God, honor and glory forever and ever. Amen. [21]

Saint Paul’s face when dictating or writing these words must have looked very much like the face of Saint Peter in Rembrandt’s painting.

Let me know what you see, my old and trustworthy friend of so many adventures. You still can startle me with your capacity to see what I have overlooked. Thank you for the years.

Love,

Rick

Notes

[1] Benezit Dictionary of Artists (Oxford Art Online) – “From the beginning of his career, Rembrandt’s choice of themes indicates his fidelity to the Bible. His desire for personal involvement often led him to invest figures from the Old Testament or the Gospels with the characteristics of his close relations…. From 1624 to 1630, in the Leiden period, he executed many compositions depicting religious subjects, bearing witness to a multidimensional period of research already influenced by the exploitation of chiaroscuro…. In the 1630s series of paintings about the life of Christ commissioned by the Prince of Orange, which is the essential element of his Baroque period, not an influence but an assimilation of Rubens’ work can be deduced, though, to the dynamic power and chromatic brilliance of Rubens, Rembrandt brought his tight lines and intense treatment of the chiaroscuro effect. In the 1630s and 1640s, encouraged by the pervading Baroque trend, Rembrandt seemed to concern himself with the expression of movement, particularly in choosing the moment within the action, the instant at which there is the most intense tension….”

[2] There are multiple titles given to this painting “Peter Denying Christ” or “The Denial of Peter” or “The Denial of Saint Peter” – I have settled on this latter one, because this is the name that is given it at the museum in Amsterdam where the painting is housed. Also, I have used AI features in Skylum’s Luminar, version 4, software to lighten the painting so that its features obscured in the “chiaroscuro” quality of the painting can better be seen, especially what is going on with Jesus behind Peter’s left shoulder and at a distance – the “turning” of Jesus towards His friend.

[3] Publisher: Lindisfarne Books (June 1, 2003); Publication Date: June 1, 2003; Print Length: 236 pages; ASIN: B008RLXELG.

[4] See: https://www.charliemackesy.com

[5] Hardcover: 128 pages; Item Weight: 13.1 ounces; ISBN-10: 0062976583; ISBN-13: 978-0062976581; Publisher: HarperOne; Illustrated Edition (October 22, 2019). This is his first book.

[6] Jon Moore-Hart, a bookish and deeply reflective man, said to me, “I have a book that you need to see. I will get it for you.” And he did. It is a luminous book by Charlie Mackesy[6] called The Boy, the Mole the Fox, and the Horse,[6] which the author dedicates with these words: “This book is dedicated to my lovely, kind mum, and my wonderful dog, Dill.” And within the opening three pages (everywhere illustrated with Mackesy’s pen and ink drawings (reminds one of the illustrations in The Little Prince), we see the little boy sitting on a tree branch with his friend, Mole, whom he has just met (their backs to us), and from whom – Mole – this question is directed to the boy.

[7] This feast day of Mary is perhaps the one that highlights that she was a human girl (!) – what other kind could there be? – of parents, Joachim and Anne, who like all parents must have wondered at her birth what her destiny would be, must have wondered at the love for her that they both felt (their only child as far as we know), never imagining that they had that much love within them to give. This particular date is, obviously, set according to the day of her (Immaculate) conception (celebrated on December 8th each year), September 8th being nine months after her conception.

[8] All four canonical Gospels tell of the denial of Peter in the garden outside of the palace of the High Priest. But it is only Luke who recalled how Jesus was physically near enough to Peter at the moment of deepest personal failure that He turned to look at Peter. I am guessing that he heard this from John, whom we know had gone as far at Peter to the palace of the High Priest and who apparently proceeded farther, into the palace itself (unlike Peter who stayed outside in the garden).

[9] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Lk 22:59–62.

[10] Britannica Online at “chiaroscuro” (literally a compound word meaning “light-dark”) notes: “Some evidence exists that ancient Greek and Roman artists used chiaroscuro effects, but in European painting the technique was first brought to its full potential by Leonardo da Vinci in the late 15th century in such paintings as his Adoration of the Magi (1481). Thereafter, chiaroscuro became a primary technique for many painters, and by the late 17th century the term was routinely used to describe any painting, drawing, or print that depended for its effect on an extensive gradation of light and darkness…. Another outstanding master of chiaroscuro was Rembrandt, who used it with remarkable psychological effect in his paintings, drawings, and etchings.”

[11] This is the second to last paragraph in the entry at “Rembrandt” from the Benezit Dictionary of Artists.

[12] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ge 1:1–5.

[13] Eugene H. Peterson, The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language (Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress, 2005), 1 Co 13:12–13. J.B. Phillips translates at the end of verse 12 in this way: “At present all I know is a little fraction of the truth, but the time will come when I shall know it as fully as God now knows me!” This rendering works particularly well with this scene, concerning Peter who does not yet fully know himself (he believes that he does!), and Jesus behind him, turning to look, Who knows Him better than Peter is yet able to know himself.

[14] The Oxford English Dictionary at the verb “to enjoin” – “In early use: To impose (a penalty, task, duty, or obligation); said esp. of a spiritual director (to enjoin penance, etc.). Hence in modern use: To prescribe authoritatively and with emphasis (an action, a course of conduct, state of feeling, etc.). Const. on, upon (a person); formerly to, or dative (or accusative: see 2b); also simply. ‘It is more authoritative than direct, and less imperious than command’ (Johnson).”

[15] “First, conversion is a complex process of transformation involving various conscious operations of the human person. Second, the phenomenon of transformation influences the personal and cultural dynamics of being and acting within history. These dynamics, such as the distorting power of bias and the clarifying venture of questioning, are themselves complex maneuvers of attention and intellect. In defining the conversion phenomenon, however, the greatest dilemma for Christian spirituality is the understanding of the operation of grace, itself an undefinable reality. Thus conversion is caught up in the mystery of grace operating within human transformation and the potentiality for persons and cultures to become a new creation.” [Michael Downey, The New Dictionary of Catholic Spirituality (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2000), 230, this particular article on “Conversion” by Richard N. Fragomani.]

[16] Of course, it is about Peter. Just ask him! What I am arguing, and I think with Rembrandt, is that much later in Peter’s life, when he had finally come to understand the depth of the divine Kindness to him, comprehended how even at that earlier moment in his life, that utterly calamitous moment when he understood that he was capable of betrayal, of that betrayal, it was even then really and always about God, Who God is, what God can will do, because of Who God is.

[17] We have to be attentive not to make “conversion” as solely, or even principally, about conversion from our sins! Our willful and habitual sinning should have been behind us long ago. Conversion for those not in the habit of sinning as a habit, as a deliberate spiritual discipline (!), know that conversion is much more about the deepening of our lives, the awakening of our soul’s powers, the expanding of our embrace of the created world and all of its creatures, and the owning of our responsibility as God’s children. In other words, conversion means a habit constituted by a deliberate choice to keep learning, to grow up, to mature … to let God have us: “to see Him more clearly / to love Him more dearly / to follow Him more nearly / day by day” as the song in Godspell goes.

g Nm 23:19; Is 31:3; Ez 28:2. [How surprised the author of Numbers, and Isaiah and Ezekiel, would have been had they known that God would become a human being, in the fullness of Time!]

[18] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ho 11:8–9.

[19] We are edging very close here to the insights of René Girard, or perhaps in specific relation to the passion and death of the Christ to the insights of Sebastian Moore, OP, The Crucified Jesus is No Stranger – a magnificent book of enormous depth.

[20] “Lovingkindness” obviously is an effort in English to give word to an experience so full that it requires two words of enormous depth of meaning to be combined. It is an effort in English to translate what the Latin misericordia means, defined by Lewis and Short, Latin Dictionary: “tender-heartedness, pity, compassion, mercy.” The Oxford English Dictionary at “lovingkindness” – “Kindness arising from love; tenderness; compassion; an instance of this.” Misericordia in Latin is that language’s effort to translate the Hebrew hesed, an impossibly rich word because used to describe the heart of God (!), but which adds to the Latin meaning, and therefore to the English “lovingkindness” the idea of “covenant faithfulness”; that is, God is to be trusted.

* This saying is trustworthy: this phrase regularly introduces in the Pastorals a basic truth of early Christian faith; cf. 1 Tm 3:1; 4:9; 2 Tm 2:11; Ti 3:8.

m Lk 15:2; 19:10.

[21] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), 1 Ti 1:12–17.

[2] There are multiple titles given to this painting “Peter Denying Christ” or “The Denial of Peter” or “The Denial of Saint Peter” – I have settled on this latter one, because this is the name that is given it at the museum in Amsterdam where the painting is housed. Also, I have used AI features in Skylum’s Luminar, version 4, software to lighten the painting so that its features obscured in the “chiaroscuro” quality of the painting can better be seen, especially what is going on with Jesus behind Peter’s left shoulder and at a distance – the “turning” of Jesus towards His friend.

[3] Publisher: Lindisfarne Books (June 1, 2003); Publication Date: June 1, 2003; Print Length: 236 pages; ASIN: B008RLXELG.

[4] See: https://www.charliemackesy.com

[5] Hardcover: 128 pages; Item Weight: 13.1 ounces; ISBN-10: 0062976583; ISBN-13: 978-0062976581; Publisher: HarperOne; Illustrated Edition (October 22, 2019). This is his first book.

[6] Jon Moore-Hart, a bookish and deeply reflective man, said to me, “I have a book that you need to see. I will get it for you.” And he did. It is a luminous book by Charlie Mackesy[6] called The Boy, the Mole the Fox, and the Horse,[6] which the author dedicates with these words: “This book is dedicated to my lovely, kind mum, and my wonderful dog, Dill.” And within the opening three pages (everywhere illustrated with Mackesy’s pen and ink drawings (reminds one of the illustrations in The Little Prince), we see the little boy sitting on a tree branch with his friend, Mole, whom he has just met (their backs to us), and from whom – Mole – this question is directed to the boy.

[7] This feast day of Mary is perhaps the one that highlights that she was a human girl (!) – what other kind could there be? – of parents, Joachim and Anne, who like all parents must have wondered at her birth what her destiny would be, must have wondered at the love for her that they both felt (their only child as far as we know), never imagining that they had that much love within them to give. This particular date is, obviously, set according to the day of her (Immaculate) conception (celebrated on December 8th each year), September 8th being nine months after her conception.

[8] All four canonical Gospels tell of the denial of Peter in the garden outside of the palace of the High Priest. But it is only Luke who recalled how Jesus was physically near enough to Peter at the moment of deepest personal failure that He turned to look at Peter. I am guessing that he heard this from John, whom we know had gone as far at Peter to the palace of the High Priest and who apparently proceeded farther, into the palace itself (unlike Peter who stayed outside in the garden).

[9] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Lk 22:59–62.

[10] Britannica Online at “chiaroscuro” (literally a compound word meaning “light-dark”) notes: “Some evidence exists that ancient Greek and Roman artists used chiaroscuro effects, but in European painting the technique was first brought to its full potential by Leonardo da Vinci in the late 15th century in such paintings as his Adoration of the Magi (1481). Thereafter, chiaroscuro became a primary technique for many painters, and by the late 17th century the term was routinely used to describe any painting, drawing, or print that depended for its effect on an extensive gradation of light and darkness…. Another outstanding master of chiaroscuro was Rembrandt, who used it with remarkable psychological effect in his paintings, drawings, and etchings.”

[11] This is the second to last paragraph in the entry at “Rembrandt” from the Benezit Dictionary of Artists.

[12] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ge 1:1–5.

[13] Eugene H. Peterson, The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language (Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress, 2005), 1 Co 13:12–13. J.B. Phillips translates at the end of verse 12 in this way: “At present all I know is a little fraction of the truth, but the time will come when I shall know it as fully as God now knows me!” This rendering works particularly well with this scene, concerning Peter who does not yet fully know himself (he believes that he does!), and Jesus behind him, turning to look, Who knows Him better than Peter is yet able to know himself.

[14] The Oxford English Dictionary at the verb “to enjoin” – “In early use: To impose (a penalty, task, duty, or obligation); said esp. of a spiritual director (to enjoin penance, etc.). Hence in modern use: To prescribe authoritatively and with emphasis (an action, a course of conduct, state of feeling, etc.). Const. on, upon (a person); formerly to, or dative (or accusative: see 2b); also simply. ‘It is more authoritative than direct, and less imperious than command’ (Johnson).”

[15] “First, conversion is a complex process of transformation involving various conscious operations of the human person. Second, the phenomenon of transformation influences the personal and cultural dynamics of being and acting within history. These dynamics, such as the distorting power of bias and the clarifying venture of questioning, are themselves complex maneuvers of attention and intellect. In defining the conversion phenomenon, however, the greatest dilemma for Christian spirituality is the understanding of the operation of grace, itself an undefinable reality. Thus conversion is caught up in the mystery of grace operating within human transformation and the potentiality for persons and cultures to become a new creation.” [Michael Downey, The New Dictionary of Catholic Spirituality (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2000), 230, this particular article on “Conversion” by Richard N. Fragomani.]

[16] Of course, it is about Peter. Just ask him! What I am arguing, and I think with Rembrandt, is that much later in Peter’s life, when he had finally come to understand the depth of the divine Kindness to him, comprehended how even at that earlier moment in his life, that utterly calamitous moment when he understood that he was capable of betrayal, of that betrayal, it was even then really and always about God, Who God is, what God can will do, because of Who God is.

[17] We have to be attentive not to make “conversion” as solely, or even principally, about conversion from our sins! Our willful and habitual sinning should have been behind us long ago. Conversion for those not in the habit of sinning as a habit, as a deliberate spiritual discipline (!), know that conversion is much more about the deepening of our lives, the awakening of our soul’s powers, the expanding of our embrace of the created world and all of its creatures, and the owning of our responsibility as God’s children. In other words, conversion means a habit constituted by a deliberate choice to keep learning, to grow up, to mature … to let God have us: “to see Him more clearly / to love Him more dearly / to follow Him more nearly / day by day” as the song in Godspell goes.

g Nm 23:19; Is 31:3; Ez 28:2. [How surprised the author of Numbers, and Isaiah and Ezekiel, would have been had they known that God would become a human being, in the fullness of Time!]

[18] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ho 11:8–9.

[19] We are edging very close here to the insights of René Girard, or perhaps in specific relation to the passion and death of the Christ to the insights of Sebastian Moore, OP, The Crucified Jesus is No Stranger – a magnificent book of enormous depth.

[20] “Lovingkindness” obviously is an effort in English to give word to an experience so full that it requires two words of enormous depth of meaning to be combined. It is an effort in English to translate what the Latin misericordia means, defined by Lewis and Short, Latin Dictionary: “tender-heartedness, pity, compassion, mercy.” The Oxford English Dictionary at “lovingkindness” – “Kindness arising from love; tenderness; compassion; an instance of this.” Misericordia in Latin is that language’s effort to translate the Hebrew hesed, an impossibly rich word because used to describe the heart of God (!), but which adds to the Latin meaning, and therefore to the English “lovingkindness” the idea of “covenant faithfulness”; that is, God is to be trusted.

* This saying is trustworthy: this phrase regularly introduces in the Pastorals a basic truth of early Christian faith; cf. 1 Tm 3:1; 4:9; 2 Tm 2:11; Ti 3:8.

m Lk 15:2; 19:10.

[21] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), 1 Ti 1:12–17.

Posted in Letters to Peregrinus, Rick Ganz

Posted in light and darkness, kindness, conversion, Rembrandt

Posted in light and darkness, kindness, conversion, Rembrandt

Recent

Categories

Tags

Archive

2026

2025

January

March

June

October

2024

January

March

September

October

2023

March

November

2022

2021

2020

No Comments