Letters to Peregrinus #38 - On a Last Thing

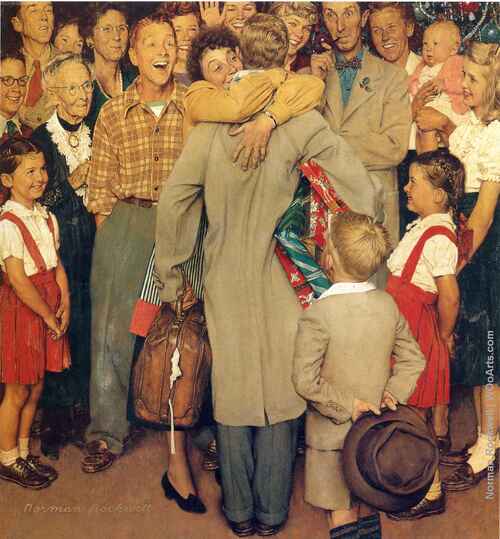

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), “Christmas Homecoming” on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post (December 1948).[1]

Dear Peregrinus (9:15 AM):

Thank you for writing recently and letting me know what you have been learning from the great René Noel Girard (1923-2015) concerning his important thoughts about “atonement.”[2] You wrote to me in October, and now, suddenly, it is November with Pacific Standard Time returning early Sunday morning.

You know of my interest in Time, but also in how we name “segments” of Time. November is a name that means “9th” even though this month is the “11th” of the year.[3] This dislocation of the month of November from 9th position to the 11th position carries within it the story of how the Calendar ceased to be connected to the Moon (the original Roman calendar established in 6th BCE) and became solely connected, by decree of Julius Caesar (in 45 BCE), with the Sun.[4]

November is the last full month in Ordinary Time according to the “liturgical calendar’ (yet another way of counting, and naming, Time), coming just before the first Sunday of Advent, which is the Christian “new year day.” [5] The “liturgical year” [6] marks six “seasons”[7]: Advent, Christmastide, Lent, Holy Triduum,[8] Eastertide, and Ordinary Time.

November has become for me the month when I have gone to school on “the November mysteries.” These mysteries are: Death, Judgement, Hell, and Heaven.[9] But while considering these “terminal” facts, I have been given understanding about what is “going forward” during such “moments” in God’s unceasing elaboration[10] of Creation.[11]The sheer richness of divine truth hidden in these mysteries has been at times almost overwhelming for me to experience. I think that they are supposed to be experienced this way by everyone.

You might be quick to ask about “Purgatory?” Among these November mysteries, why is there no inclusion of “Purgatory”, which is something about which Christians, and artists, have for centuries demonstrated a particular curiosity?

But for a person to ask about Purgatory’s apparent absence in the list of the “last things” reveals his or her misunderstanding of something essential about Heaven, where by “heaven” I mean a way a person experiences his or her relationship with God “there”, either in a blissful way or in a still “uneasy” way. Consider the kind of relationship Jesus Himself prays will come about “in Heaven”:

Purgatory is a doctrine that reveals something important about Heaven, or better, a doctrine that is cognizant of the different ways a person experiences Heaven[14] when welcomed there[15] through an un-earned gift extended him or her by God - of being enfolded within the mutual indwelling of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. To wonder about Purgatory is to wonder about Heaven – the latter encapsulates the reality of the former.

I did not always understand it this way. What I understood Purgatory to mean when I was a boy, and then well into my years as a Jesuit, can be summarized in the following three points.[16]

First, I understood Purgatory as a place,[17] located in-between[18] Heaven and Hell (getting kind of crowded in that space, because our world had to fit in-between there too!), where the status of our salvation was still unsettled – “Will I go to Hell, or will I get to go to Heaven?”.[19] Second, I was taught that this in-between place was an arena where punishments were meted out by God … because such punishments were supposed to “purify” my soul, making it “worthy” to be with God forever, in Heaven. (It left my boy-mind unsettled when I wondered why I wanted to be forever with a God Who promised me love, even as I perceived Him as so creative in finding ways to make me hurt.) Third, I was taught the importance of praying for “the poor souls” in Purgatory, which to my boy-mind suggested that Purgatory was a place of great danger, a place where “the poor souls” did not have what they needed (within themselves or from God) to reach Heaven. We had to pray for them, lest lacking our prayers they would be forever lost! (This left my boy-mind unsettled again because it suggested to me that those in Purgatory had been stripped of sufficient means to “earn” their way into Heaven, making Purgatory a place even more lacking in essential resources than what they had possessed here on Earth.)

Does this summary pretty well describe what you thought too, old friend? What is your current thinking about the “November mysteries”? Here are three thoughts that I am exploring.

First, it clear that we are well able to earn eternal damnation. That is in our power to bring about.[20] However, it is just not true that we can earn Heaven, either by good works or by maintaining perfect moral excellence. Heaven is impossible to earn, which is perhaps its most startling aspect. To be invited into so intimate a relationship with the Triune God, and the opening to this won for us in Christ, is pure gift.

Second, the Church’s teaching is clear that if we have been granted access into Purgatory, then we know that we have been given the gift of Heaven, and even now “stand within the grace” of perfect beatitude. The drama of our salvation has been settled. There remains no uncertainty as to whether we have been granted a place with God, to be eternally “where” God abides in glory. But (and here is the center of the Church’s insight – sourced in the teaching of St. Catherine of Genoa[22]), we may experience ourselves sitting “uncomfortably” within this degree of intimacy offered us by God. “It takes some getting used to,” we might say. Such closeness to LOVE itself unsettles us, profoundly, and we wish it did not. “Love bade me welcome / but my soul drew back”, as the famous poem by George Herbert begins.[23] In this regard, we may consider Purgatory as the extending to us by God of a profound courtesy. We need “time” to adjust to Him.

Third, the “purgation” of Purgatory (i.e., the soul in the process of being made completely available to the divine intimacy) is an experience of JOY so intense as to make any joy we experienced in our earthly life a shadow-joy. The JOY supplies to us the motivation to let happen what needs to happen “there.” St. Catherine of Genoa puts it this way: “There is no joy, save that in Paradise, to be compared to the joy of the souls in Purgatory.” Why this? And what of the famous “pain” of Purgatory? I say this. We experience JOY in the purgation we are experiencing, because finally we know, and for certain, that the Trinity itself “has us.” The initiative is now completely with God. At one and the same “moment”, we feel LOVE burning us into a more complete openness to receive it – “be it done unto me according to your word,” as Mary said to the Archangel – but also we feel how comprehensively unable we are without God’s help to respond adequately to such divine closeness. This inability to receive all God wishes to give us we experience as a profound limitation, which causes us intense inner pain - a purest form of self-disappointment. But that self-disappointment is the last vestige in our soul of ego, of self-love (that undying foe of the soul!) wanting to earn Heaven, wanting to be sufficient to what is offered us. But, Heaven will be experienced as GIFT, complete and utter, or not at all.

In conclusion, old friend, I leave you with a prayer from the holiest man I ever personally met, a man whose holiness was the most forward and obvious quality about him. In this prayer, or expression of insight, which he wrote after suffering a stroke that rendered that eloquent man speechless for the last ten years before he died, is a beautiful expression of the “purgation” of Purgatory:

Let us meet in prayer, dear friend. May God bless us in this year’s exploration of “the November mysteries.”

I am your old friend on the pilgrim’s road,

Rick, SJ

Thank you for writing recently and letting me know what you have been learning from the great René Noel Girard (1923-2015) concerning his important thoughts about “atonement.”[2] You wrote to me in October, and now, suddenly, it is November with Pacific Standard Time returning early Sunday morning.

You know of my interest in Time, but also in how we name “segments” of Time. November is a name that means “9th” even though this month is the “11th” of the year.[3] This dislocation of the month of November from 9th position to the 11th position carries within it the story of how the Calendar ceased to be connected to the Moon (the original Roman calendar established in 6th BCE) and became solely connected, by decree of Julius Caesar (in 45 BCE), with the Sun.[4]

November is the last full month in Ordinary Time according to the “liturgical calendar’ (yet another way of counting, and naming, Time), coming just before the first Sunday of Advent, which is the Christian “new year day.” [5] The “liturgical year” [6] marks six “seasons”[7]: Advent, Christmastide, Lent, Holy Triduum,[8] Eastertide, and Ordinary Time.

November has become for me the month when I have gone to school on “the November mysteries.” These mysteries are: Death, Judgement, Hell, and Heaven.[9] But while considering these “terminal” facts, I have been given understanding about what is “going forward” during such “moments” in God’s unceasing elaboration[10] of Creation.[11]The sheer richness of divine truth hidden in these mysteries has been at times almost overwhelming for me to experience. I think that they are supposed to be experienced this way by everyone.

37 No, in all these things we conquer overwhelmingly through him who loved us.c 38 For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor present things,* nor future things, nor powers,d 39 nor height, nor depth,* nor any other creature will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord. [12]

You might be quick to ask about “Purgatory?” Among these November mysteries, why is there no inclusion of “Purgatory”, which is something about which Christians, and artists, have for centuries demonstrated a particular curiosity?

But for a person to ask about Purgatory’s apparent absence in the list of the “last things” reveals his or her misunderstanding of something essential about Heaven, where by “heaven” I mean a way a person experiences his or her relationship with God “there”, either in a blissful way or in a still “uneasy” way. Consider the kind of relationship Jesus Himself prays will come about “in Heaven”:

24 Father, they are your gift to me. I wish that where I am* they also may be with me, that they may see my glory that you gave me, because you loved me before the foundation of the world.n 25 Righteous Father, the world also does not know you, but I know you, and they know that you sent me.o 26 I made known to them your name and I will make it known,* that the love with which you loved me may be in them and I in them.” [13]

Purgatory is a doctrine that reveals something important about Heaven, or better, a doctrine that is cognizant of the different ways a person experiences Heaven[14] when welcomed there[15] through an un-earned gift extended him or her by God - of being enfolded within the mutual indwelling of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. To wonder about Purgatory is to wonder about Heaven – the latter encapsulates the reality of the former.

I did not always understand it this way. What I understood Purgatory to mean when I was a boy, and then well into my years as a Jesuit, can be summarized in the following three points.[16]

First, I understood Purgatory as a place,[17] located in-between[18] Heaven and Hell (getting kind of crowded in that space, because our world had to fit in-between there too!), where the status of our salvation was still unsettled – “Will I go to Hell, or will I get to go to Heaven?”.[19] Second, I was taught that this in-between place was an arena where punishments were meted out by God … because such punishments were supposed to “purify” my soul, making it “worthy” to be with God forever, in Heaven. (It left my boy-mind unsettled when I wondered why I wanted to be forever with a God Who promised me love, even as I perceived Him as so creative in finding ways to make me hurt.) Third, I was taught the importance of praying for “the poor souls” in Purgatory, which to my boy-mind suggested that Purgatory was a place of great danger, a place where “the poor souls” did not have what they needed (within themselves or from God) to reach Heaven. We had to pray for them, lest lacking our prayers they would be forever lost! (This left my boy-mind unsettled again because it suggested to me that those in Purgatory had been stripped of sufficient means to “earn” their way into Heaven, making Purgatory a place even more lacking in essential resources than what they had possessed here on Earth.)

Does this summary pretty well describe what you thought too, old friend? What is your current thinking about the “November mysteries”? Here are three thoughts that I am exploring.

First, it clear that we are well able to earn eternal damnation. That is in our power to bring about.[20] However, it is just not true that we can earn Heaven, either by good works or by maintaining perfect moral excellence. Heaven is impossible to earn, which is perhaps its most startling aspect. To be invited into so intimate a relationship with the Triune God, and the opening to this won for us in Christ, is pure gift.

12 I am grateful to him who has strengthened me, Christ Jesus our Lord, because he considered me trustworthy in appointing me to the ministry.j 13 I was once a blasphemer and a persecutor and an arrogant man, but I have been mercifully treated because I acted out of ignorance in my unbelief.k 14 Indeed, the grace of our Lord has been abundant, along with the faith and love that are in Christ Jesus.l 15 This saying is trustworthy* and deserves full acceptance: Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners. Of these I am the foremost.m 16 But for that reason I was mercifully treated, so that in me, as the foremost, Christ Jesus might display all his patience as an example for those who would come to believe in him for everlasting life. 17 To the king of ages,* incorruptible, invisible, the only God, honor and glory forever and ever. Amen.n [21]

Second, the Church’s teaching is clear that if we have been granted access into Purgatory, then we know that we have been given the gift of Heaven, and even now “stand within the grace” of perfect beatitude. The drama of our salvation has been settled. There remains no uncertainty as to whether we have been granted a place with God, to be eternally “where” God abides in glory. But (and here is the center of the Church’s insight – sourced in the teaching of St. Catherine of Genoa[22]), we may experience ourselves sitting “uncomfortably” within this degree of intimacy offered us by God. “It takes some getting used to,” we might say. Such closeness to LOVE itself unsettles us, profoundly, and we wish it did not. “Love bade me welcome / but my soul drew back”, as the famous poem by George Herbert begins.[23] In this regard, we may consider Purgatory as the extending to us by God of a profound courtesy. We need “time” to adjust to Him.

Third, the “purgation” of Purgatory (i.e., the soul in the process of being made completely available to the divine intimacy) is an experience of JOY so intense as to make any joy we experienced in our earthly life a shadow-joy. The JOY supplies to us the motivation to let happen what needs to happen “there.” St. Catherine of Genoa puts it this way: “There is no joy, save that in Paradise, to be compared to the joy of the souls in Purgatory.” Why this? And what of the famous “pain” of Purgatory? I say this. We experience JOY in the purgation we are experiencing, because finally we know, and for certain, that the Trinity itself “has us.” The initiative is now completely with God. At one and the same “moment”, we feel LOVE burning us into a more complete openness to receive it – “be it done unto me according to your word,” as Mary said to the Archangel – but also we feel how comprehensively unable we are without God’s help to respond adequately to such divine closeness. This inability to receive all God wishes to give us we experience as a profound limitation, which causes us intense inner pain - a purest form of self-disappointment. But that self-disappointment is the last vestige in our soul of ego, of self-love (that undying foe of the soul!) wanting to earn Heaven, wanting to be sufficient to what is offered us. But, Heaven will be experienced as GIFT, complete and utter, or not at all.

In conclusion, old friend, I leave you with a prayer from the holiest man I ever personally met, a man whose holiness was the most forward and obvious quality about him. In this prayer, or expression of insight, which he wrote after suffering a stroke that rendered that eloquent man speechless for the last ten years before he died, is a beautiful expression of the “purgation” of Purgatory:

Pedro Arrupe, SJ (1907-1991)

More than ever I find myself in the hands of God.

This is what I have wanted all my life from my youth.

But now there is a difference;

the initiative is entirely with God.

It is indeed a profound spiritual experience

to know and feel myself so totally in God’s hands.

Let us meet in prayer, dear friend. May God bless us in this year’s exploration of “the November mysteries.”

I am your old friend on the pilgrim’s road,

Rick, SJ

Notes

[1] See at the Norman Rockwell Museum: https://www.nrm.org/christmas_homecoming_web/. The Museum is located in Stockbridge, MA. Norman Percevel Rockwell died on 8 November 1978, about whom Christopher Brookeman writes, in part: “Rockwell undoubtedly had great influence in creating an image of liberal, middle-class, conservative America…. His work provides a fascinating window into changes and continuities in American ideology in the 20th century.” See Brookeman, C. (1 January 2003) at: http:////www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000072540.

[2] See, for example, the theologian James Allison (a thinker deeply reliant on thoughts from Girard) when he write his summary of his book On Being Liked (2004) – “First in importance in my own mind is the ‘salvation’ triptych (chapters 2, 3 and 4). It seems to me that one of the things that we are still flailing about looking for in the aftermath of the Second Vatican Council [1962-1965] is an account of our salvation which makes sense to us. The old default account, common to both Catholic and Protestant ‘orthodoxy’ was some variation on the substitionary theory of the atonement. That is, some version of a tale in which Jesus died for us, instead of us who really deserved it, so as to pay a bill for sin that we could not pay, but for whose settlement God himself immutably demanded payment. Not only does this not make sense, but it is scandalous in a variety of ways. It has been one of the principal merits of the thought of René Girard that, at last, it is enabling us to scrabble towards a new account of how we are being saved which is free from the long shadow of pagan sacrificial attitudes and practice. So, first of all I engage in a deconstruction of the old sacrificial way of understanding salvation, and the nasty little bits of residue it still leaves and which get in the way of our capacity to tell a properly Catholic story (chapter 2).”

[3] See https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/months/november.html – “November was originally the 9th month of early versions of the Roman calendar and consisted of 30 days. It became the 11th month of the year with a length of 29 days when the months of January and February were added. During the Julian calendar reform, a day was added to November making it 30 days long again.”

[4] https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/julian-calendar.html - “The Julian calendar's predecessor, the Roman calendar, was a very complicated lunar calendar, based on the moon phases. It required a group of people to decide when days should be added or removed in order to keep the calendar in sync with the astronomical seasons, marked by equinoxes and solstices. In order to create a more standardized calendar, Julius Caesar consulted an Alexandrian astronomer named Sosigenes and created a more regulated civil calendar, a solar calendar based entirely on Earth's revolutions around the Sun, also called a tropical year. It takes our planet on average, approximately 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes and 45 seconds (365.242189 days) to complete one full orbit around the Sun.”

[5] The Christian “new year day” begins each year on the first Sunday of Advent. For many centuries “new year day” was on March 25th – the traditional day “when the Angel declared unto Mary” (the feast of the Incarnation). But eventually it was not the conception of Jesus in the womb of Mary (the Annunciation) that had pride of place in the Liturgical Calendar – “Let it be done to me / according to your will” – but rather the birth of Jesus, in the manger, in Bethlehem of Judaea, that took pride of place, and the season of Advent preparation set in relation to Christmas Day – “and the Word became flesh / and dwelt among us.”

[6] For example, see http://www.usccb.org/prayer-and-worship/liturgical-year/index.cfm.

[7] The Oxford English Dictionary notes in the etymology of this noun “season” - < Latin satiōn-em act of sowing (in vulgar Latin time of sowing, seed-time), noun of action < sa- root of serĕre to sow.

[8] The “holy Triduum” means literally, “the holy three days”. It refers to: Day One: from Holy Thursday evening to Good Friday evening; Day Two: from Good Friday evening to Holy Saturday evening; Day Three: from Holy Saturday evening to Easter Sunday evening. These days, after the custom of the Jewish understanding, are counted from sundown to sundown. Recall, for example, how the weekly Sabbath commences with sundown each Friday evening.

[9] For example, see https://www.ewtn.com/faith/teachings/lastsum.htm.

[10] The Oxford English Dictionary concerning the 17th century verb “to elaborate” defines it, in its original meaning: “To produce or develop by the application of labour; to fashion (a product of art or industry) from the raw material; to work out in detail, give finish or completeness to (an invention, a theory, literary or artistic work, etc.).”

[11] This is a very important point about the “End of Days”. Ever since God “learned” of His capacity to destroy the created world, and within just a few people and animals from completely, God promised (Genesis 9:11-17 - recall the rainbow God causes to appear in the heavens as a Sign) that He would never again destroy what He had created. Therefore the “End of Days” cannot be about the destruction of the created universe, but must be about the “bringing forward” of the created universe into an unimaginable luminosity – a kind of “resurrection” of Creation itself.

c 1 Jn 5:4.

* Present things and future things may refer to astrological data. Paul appears to be saying that the gospel liberates believers from dependence on astrologers.

d 1 Cor 3:22; Eph 1:21; 1 Pt 3:22.

* Height, depth may refer to positions in the zodiac, positions of heavenly bodies relative to the horizon. In astrological documents the term for “height” means “exaltation” or the position of greatest influence exerted by a planet. Since hostile spirits were associated with the planets and stars, Paul includes powers (Rom 8:38) in his list of malevolent forces.

[12] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ro 8:37–39.

* Where I am: Jesus prays for the believers ultimately to join him in heaven. Then they will not see his glory as in a mirror but clearly (2 Cor 3:18; 1 Jn 3:2).

n 14:3; 1 Thes 4:17.

o 1:10.

* I will make it known: through the Advocate.

[13] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Jn 17:24–26.

[14] The remotest source of my own insight into this is C.S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce (1945). The book was first printed as a serial in an Anglican newspaper called The Guardian in 1944 and 1945, and soon thereafter in book form. See, for example, Bishop Barron’s homage to this book (which I consider one of Lewis’ greatest) at: https://www.wordonfire.org/resources/article/why-you-should-read-cs-lewis-the-great-divorce/5128/, where he writes, in part: “All of Hell, which seemed so immense to the narrator, would fit into a practically microscopic space in Heaven. Lewis is illustrating here the Augustinian principle that sin is the state of being incurvatus in se (curved in around oneself). It is the reduction of reality to the infinitely small space of the ego’s concerns and preoccupations. Love, on the contrary, which is the very life of Heaven, is the opening to reality in its fullness; it amounts to a breaking through of the buffered and claustrophobic self; it is the activity of the magna anima (the great soul). We think our own little ego-centric worlds are so impressive, but to those who are truly open to reality, they are less than nothing.”

[15] That adverb “there” is already misdirecting our understanding of this important insight into the nature of God. It is an adverb of spatial location: there not here, for example. But Purgatory is not a “place”, and thinking so (as so many artists through the ages have delighted to paint it as such) is significantly misleading.

[16] It is striking to me that once I left my boyhood Teachers – those who taught me when I was in grade school – I have never again heard any significant teaching about the Last Things by any Teacher … except the one time when I was required during my Theology studies to take a Course on Eschatology – the study of the “last things.” Part of my commitment to lean into the “November mysteries” some seven years ago had its source in my awareness of how comprehensively we all avoided thinking about these matters!

[17] It is interesting to recall that when Pope John Paul II, now a canonized Saint of the Church, gave a series of Talks in the late summer and early autumn of 1999 on the “last things”. He caused a stir among traditionalists when he articulated this very point; namely, that Heaven and Hell and Purgatory are not places, but words that describe “states” of human being in relation to the Last Things.

[18] Purgatory is properly understood as “in-between” if one grasps it as a metaphor for an intermediate state of human existence, rather than as an indicator of a location to which humans might proceed after death. Purgatory, as I will explain, is a way of speaking about a person who experiences Heaven as simply too overwhelming, not primarily because he or she is bad, but primarily because God is so true and beautiful and good … so BIG and I so small.

[19] Pope John Paul II in those Talks he gave in 1999 goes after this profound misunderstanding when speaking of Purgatory (4 August 1999) he wrote: “It is necessary to explain that the state of purification is not a prolongation of the earthly condition, almost as if after death one were given another possibility to change one's destiny. The Church's teaching in this regard is unequivocal and was reaffirmed by the Second Vatican Council….”

[20] What remains uncomfortable to me in saying this so unequivocally – we can earn our damnation – is based on a conviction (possibly very wrong) that it is possible for us to be absolutely solitary, to achieve a complete aloneness … such that I alone have such comprehensive ownership of myself as to be able to dispose of myself in this absolute way. When I think of my own sinfulness, I cannot help remembering how there are many who love and believe in me anyway. In this regard I “belong” to them, meaning that their hope for me matters significantly, and matters to God. Would God allow me, or anyone, the power to cast himself or herself into Hell’s terminal superficiality, when He sees how I belong to whose who love and believe in me? It is a puzzle to me.

j Phil 4:13 / Acts 9:15; Gal 1:15–16.

k Acts 8:3; 9:1–2; 1 Cor 15:9; Gal 1:13.

l Rom 5:20; 2 Tm 1:13.

* This saying is trustworthy: this phrase regularly introduces in the Pastorals a basic truth of early Christian faith; cf. 1 Tm 3:1; 4:9; 2 Tm 2:11; Ti 3:8.

m Lk 15:2; 19:10.

* King of ages: through Semitic influence, the Greek expression could mean “everlasting king”; it could also mean “king of the universe.”

n Rom 16:27.

[21] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), 1 Ti 1:12–17.

[22] The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 3rd edition (2005): Catherine, St, of Genoa (1447–1510), mystic. Caterina Fieschi was of a noble Ligurian family….” Pope Benedict XVI wrote of her in January 2011, explaining the “newness” of insight about Purgatory that Catherine gave so compelling to the Church. For Catherine, purgation happens within the soul (not to body and soul in a “place” called Purgatory). Purgatory is the inner experience of being divinely blessed with a love of God (both from God and for God) so intense, that it is experienced as an unstoppable “fire” within the soul, an unstoppable divine grace in the soul that makes the soul available to receive the divine Presence to the degree that God wishes to share it.

[23] See at The Poetry Foundation for George Herbert’s poem, “Love III: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44367/love-iii.

[2] See, for example, the theologian James Allison (a thinker deeply reliant on thoughts from Girard) when he write his summary of his book On Being Liked (2004) – “First in importance in my own mind is the ‘salvation’ triptych (chapters 2, 3 and 4). It seems to me that one of the things that we are still flailing about looking for in the aftermath of the Second Vatican Council [1962-1965] is an account of our salvation which makes sense to us. The old default account, common to both Catholic and Protestant ‘orthodoxy’ was some variation on the substitionary theory of the atonement. That is, some version of a tale in which Jesus died for us, instead of us who really deserved it, so as to pay a bill for sin that we could not pay, but for whose settlement God himself immutably demanded payment. Not only does this not make sense, but it is scandalous in a variety of ways. It has been one of the principal merits of the thought of René Girard that, at last, it is enabling us to scrabble towards a new account of how we are being saved which is free from the long shadow of pagan sacrificial attitudes and practice. So, first of all I engage in a deconstruction of the old sacrificial way of understanding salvation, and the nasty little bits of residue it still leaves and which get in the way of our capacity to tell a properly Catholic story (chapter 2).”

[3] See https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/months/november.html – “November was originally the 9th month of early versions of the Roman calendar and consisted of 30 days. It became the 11th month of the year with a length of 29 days when the months of January and February were added. During the Julian calendar reform, a day was added to November making it 30 days long again.”

[4] https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/julian-calendar.html - “The Julian calendar's predecessor, the Roman calendar, was a very complicated lunar calendar, based on the moon phases. It required a group of people to decide when days should be added or removed in order to keep the calendar in sync with the astronomical seasons, marked by equinoxes and solstices. In order to create a more standardized calendar, Julius Caesar consulted an Alexandrian astronomer named Sosigenes and created a more regulated civil calendar, a solar calendar based entirely on Earth's revolutions around the Sun, also called a tropical year. It takes our planet on average, approximately 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes and 45 seconds (365.242189 days) to complete one full orbit around the Sun.”

[5] The Christian “new year day” begins each year on the first Sunday of Advent. For many centuries “new year day” was on March 25th – the traditional day “when the Angel declared unto Mary” (the feast of the Incarnation). But eventually it was not the conception of Jesus in the womb of Mary (the Annunciation) that had pride of place in the Liturgical Calendar – “Let it be done to me / according to your will” – but rather the birth of Jesus, in the manger, in Bethlehem of Judaea, that took pride of place, and the season of Advent preparation set in relation to Christmas Day – “and the Word became flesh / and dwelt among us.”

[6] For example, see http://www.usccb.org/prayer-and-worship/liturgical-year/index.cfm.

[7] The Oxford English Dictionary notes in the etymology of this noun “season” - < Latin satiōn-em act of sowing (in vulgar Latin time of sowing, seed-time), noun of action < sa- root of serĕre to sow.

[8] The “holy Triduum” means literally, “the holy three days”. It refers to: Day One: from Holy Thursday evening to Good Friday evening; Day Two: from Good Friday evening to Holy Saturday evening; Day Three: from Holy Saturday evening to Easter Sunday evening. These days, after the custom of the Jewish understanding, are counted from sundown to sundown. Recall, for example, how the weekly Sabbath commences with sundown each Friday evening.

[9] For example, see https://www.ewtn.com/faith/teachings/lastsum.htm.

[10] The Oxford English Dictionary concerning the 17th century verb “to elaborate” defines it, in its original meaning: “To produce or develop by the application of labour; to fashion (a product of art or industry) from the raw material; to work out in detail, give finish or completeness to (an invention, a theory, literary or artistic work, etc.).”

[11] This is a very important point about the “End of Days”. Ever since God “learned” of His capacity to destroy the created world, and within just a few people and animals from completely, God promised (Genesis 9:11-17 - recall the rainbow God causes to appear in the heavens as a Sign) that He would never again destroy what He had created. Therefore the “End of Days” cannot be about the destruction of the created universe, but must be about the “bringing forward” of the created universe into an unimaginable luminosity – a kind of “resurrection” of Creation itself.

c 1 Jn 5:4.

* Present things and future things may refer to astrological data. Paul appears to be saying that the gospel liberates believers from dependence on astrologers.

d 1 Cor 3:22; Eph 1:21; 1 Pt 3:22.

* Height, depth may refer to positions in the zodiac, positions of heavenly bodies relative to the horizon. In astrological documents the term for “height” means “exaltation” or the position of greatest influence exerted by a planet. Since hostile spirits were associated with the planets and stars, Paul includes powers (Rom 8:38) in his list of malevolent forces.

[12] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Ro 8:37–39.

* Where I am: Jesus prays for the believers ultimately to join him in heaven. Then they will not see his glory as in a mirror but clearly (2 Cor 3:18; 1 Jn 3:2).

n 14:3; 1 Thes 4:17.

o 1:10.

* I will make it known: through the Advocate.

[13] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), Jn 17:24–26.

[14] The remotest source of my own insight into this is C.S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce (1945). The book was first printed as a serial in an Anglican newspaper called The Guardian in 1944 and 1945, and soon thereafter in book form. See, for example, Bishop Barron’s homage to this book (which I consider one of Lewis’ greatest) at: https://www.wordonfire.org/resources/article/why-you-should-read-cs-lewis-the-great-divorce/5128/, where he writes, in part: “All of Hell, which seemed so immense to the narrator, would fit into a practically microscopic space in Heaven. Lewis is illustrating here the Augustinian principle that sin is the state of being incurvatus in se (curved in around oneself). It is the reduction of reality to the infinitely small space of the ego’s concerns and preoccupations. Love, on the contrary, which is the very life of Heaven, is the opening to reality in its fullness; it amounts to a breaking through of the buffered and claustrophobic self; it is the activity of the magna anima (the great soul). We think our own little ego-centric worlds are so impressive, but to those who are truly open to reality, they are less than nothing.”

[15] That adverb “there” is already misdirecting our understanding of this important insight into the nature of God. It is an adverb of spatial location: there not here, for example. But Purgatory is not a “place”, and thinking so (as so many artists through the ages have delighted to paint it as such) is significantly misleading.

[16] It is striking to me that once I left my boyhood Teachers – those who taught me when I was in grade school – I have never again heard any significant teaching about the Last Things by any Teacher … except the one time when I was required during my Theology studies to take a Course on Eschatology – the study of the “last things.” Part of my commitment to lean into the “November mysteries” some seven years ago had its source in my awareness of how comprehensively we all avoided thinking about these matters!

[17] It is interesting to recall that when Pope John Paul II, now a canonized Saint of the Church, gave a series of Talks in the late summer and early autumn of 1999 on the “last things”. He caused a stir among traditionalists when he articulated this very point; namely, that Heaven and Hell and Purgatory are not places, but words that describe “states” of human being in relation to the Last Things.

[18] Purgatory is properly understood as “in-between” if one grasps it as a metaphor for an intermediate state of human existence, rather than as an indicator of a location to which humans might proceed after death. Purgatory, as I will explain, is a way of speaking about a person who experiences Heaven as simply too overwhelming, not primarily because he or she is bad, but primarily because God is so true and beautiful and good … so BIG and I so small.

[19] Pope John Paul II in those Talks he gave in 1999 goes after this profound misunderstanding when speaking of Purgatory (4 August 1999) he wrote: “It is necessary to explain that the state of purification is not a prolongation of the earthly condition, almost as if after death one were given another possibility to change one's destiny. The Church's teaching in this regard is unequivocal and was reaffirmed by the Second Vatican Council….”

[20] What remains uncomfortable to me in saying this so unequivocally – we can earn our damnation – is based on a conviction (possibly very wrong) that it is possible for us to be absolutely solitary, to achieve a complete aloneness … such that I alone have such comprehensive ownership of myself as to be able to dispose of myself in this absolute way. When I think of my own sinfulness, I cannot help remembering how there are many who love and believe in me anyway. In this regard I “belong” to them, meaning that their hope for me matters significantly, and matters to God. Would God allow me, or anyone, the power to cast himself or herself into Hell’s terminal superficiality, when He sees how I belong to whose who love and believe in me? It is a puzzle to me.

j Phil 4:13 / Acts 9:15; Gal 1:15–16.

k Acts 8:3; 9:1–2; 1 Cor 15:9; Gal 1:13.

l Rom 5:20; 2 Tm 1:13.

* This saying is trustworthy: this phrase regularly introduces in the Pastorals a basic truth of early Christian faith; cf. 1 Tm 3:1; 4:9; 2 Tm 2:11; Ti 3:8.

m Lk 15:2; 19:10.

* King of ages: through Semitic influence, the Greek expression could mean “everlasting king”; it could also mean “king of the universe.”

n Rom 16:27.

[21] New American Bible, Revised Edition. (Washington, DC: The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), 1 Ti 1:12–17.

[22] The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 3rd edition (2005): Catherine, St, of Genoa (1447–1510), mystic. Caterina Fieschi was of a noble Ligurian family….” Pope Benedict XVI wrote of her in January 2011, explaining the “newness” of insight about Purgatory that Catherine gave so compelling to the Church. For Catherine, purgation happens within the soul (not to body and soul in a “place” called Purgatory). Purgatory is the inner experience of being divinely blessed with a love of God (both from God and for God) so intense, that it is experienced as an unstoppable “fire” within the soul, an unstoppable divine grace in the soul that makes the soul available to receive the divine Presence to the degree that God wishes to share it.

[23] See at The Poetry Foundation for George Herbert’s poem, “Love III: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44367/love-iii.

Recent

Categories

Tags

Archive

2026

January

2025

January

March

June

October

2024

January

March

September

October

2023

March

November

2022

2021

2020

2019

No Comments